Fecha de recepción: 04/10/2018 – Fecha de aceptación: 29/10/2018

Santiuste Román A, Montero Hernández M, López Sánchez EV, Soler Company E

Hospital Arnau de Vilanova. Valencia (España)

____

Correspondencia:

Álvar Santiuste Román w Hospital Arnau de Vilanova w C/San Clemente 12 w 46015 Valencia (España)

alvar_sanro5@hotmail.com

____

Summary

Fungal keratitis is a dangerous condition that can cause sight problems and even blindness. Fusarium solani is a kind of filamentous fungus which can cause this rare but important eye infection. Inmunosuppressive therapy and use of contact lenses have increased the incidence. In this article we report two cases of Fusarium solani fungal keratitis in inmunocompetent patients. They were first treated with different antimicrobial and antiparasitic eye drops (most of them formulated in the Pharmacy Service), until fungal infection was discovered. Natamycin was the election drug and was provided from the Pharmacy Service when purchased. Both patients improved from their patology and fungal keratitis was resumed.

Key Words: Fungal keratitis, Fusarium solani, natamycin.

____

INTRODUCTION

Eye infections are the second leading cause of blindness in the world, only surpassed by cataracts. Fungal keratitis accounts for 5-10% of eye infections1, and are commonly caused by yeast such as Candida and filamentous fungi such as Aspergillus and Fusarium2.

This infections can be caused by either corneal traumatism with organic material or by the misuse and improper care of contact lenses2.

Fusarium is a gender of universally distributed filamentous fungi, common herbal pathogens. Infections caused by this type of fungus are usually described in immunocompromised patients, but can lead to high severity in immunocompetent patients if not promptly diagnosed and treated3. Fusarium solani represents about 50% of Fusarium fungal keratitis reported cases. It is associated with longer healing time and worse prognosis in the correction of visual acuity lost during infection4.

Below are reported two cases of Fusarium solani fungal keratitis treated with topical natamycin.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

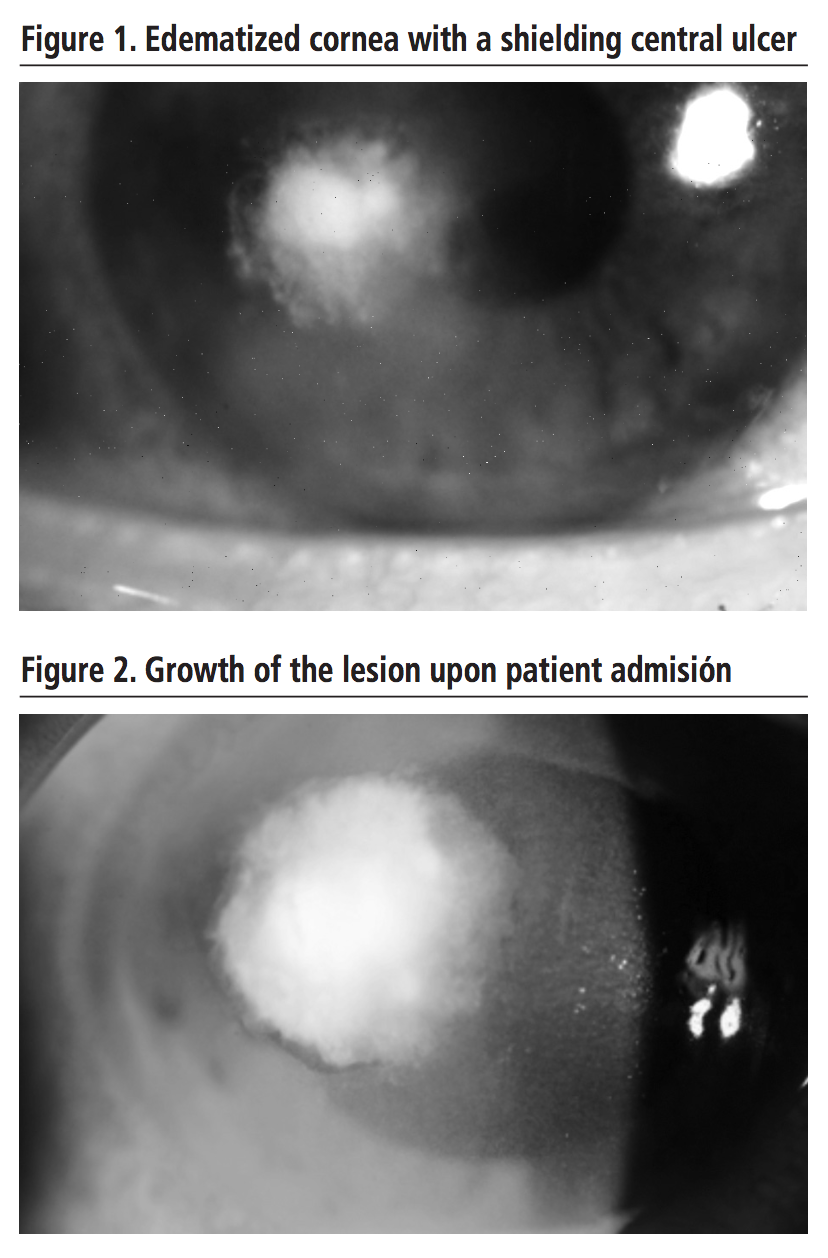

A 38-year-old male patient, single-eye (right) and contact lens wearer attended the emergency services with a one-week history of red eye and foreign body feeling that was being treated with ciprofloxacin 3 mg/ml and diclofenac 1 mg/ml eye drops. On examination, an edematized cornea with a shielding central ulcer, Tyndall negative, was observed (Figure 1).  Faced with the clinical worsening of the patient 7 days later (growth of the lesion, Tyndall positive – Figure 2) hospital admission was decided for sample collection and better control. The antibiotic treatment was modified for vancomycin and ceftazidime 50 mg/ml eye drops hourly. On the suspicion of infection by Acanthamoeba on the 10th day, treatment with chlorhexidine 0.2 mg/ml and hexamidine 15 mg/ml eye drops every 8 hours was added. Additionally, suspecting fungal infection, voriconazole 10 mg/ml eye drops hourly, were also added. This treatment was held until day 14, when culture revealed an infection by Fusarium solani. It was decided then to discontinue the antiparasitic treatment; natamycin 50 mg/ml eye drops plus oral voriconazole theraphy was started. On day 22, due to clinical improvement, the patient was discharged with topical voriconazole and natamycin. In subsequent reviews, debridement of the corneal necrotic material was required to improve ocular penetration of topical drugs Antimicrobial eye drops treatment was spaced until discontinuation, remaining the patient with anti-inflammatory and corticosteroids eye drops. Over this 8-month period, although the antimicrobial treatment was effective, the patient’s visual acuity did not significantly improve, so it was decided to place an intracorneal lens to enhance vision. In the last medical examination, a relatively dense paracentral leukoma persisted in the center of the cornea (Figure 3).

Faced with the clinical worsening of the patient 7 days later (growth of the lesion, Tyndall positive – Figure 2) hospital admission was decided for sample collection and better control. The antibiotic treatment was modified for vancomycin and ceftazidime 50 mg/ml eye drops hourly. On the suspicion of infection by Acanthamoeba on the 10th day, treatment with chlorhexidine 0.2 mg/ml and hexamidine 15 mg/ml eye drops every 8 hours was added. Additionally, suspecting fungal infection, voriconazole 10 mg/ml eye drops hourly, were also added. This treatment was held until day 14, when culture revealed an infection by Fusarium solani. It was decided then to discontinue the antiparasitic treatment; natamycin 50 mg/ml eye drops plus oral voriconazole theraphy was started. On day 22, due to clinical improvement, the patient was discharged with topical voriconazole and natamycin. In subsequent reviews, debridement of the corneal necrotic material was required to improve ocular penetration of topical drugs Antimicrobial eye drops treatment was spaced until discontinuation, remaining the patient with anti-inflammatory and corticosteroids eye drops. Over this 8-month period, although the antimicrobial treatment was effective, the patient’s visual acuity did not significantly improve, so it was decided to place an intracorneal lens to enhance vision. In the last medical examination, a relatively dense paracentral leukoma persisted in the center of the cornea (Figure 3).

Case 2

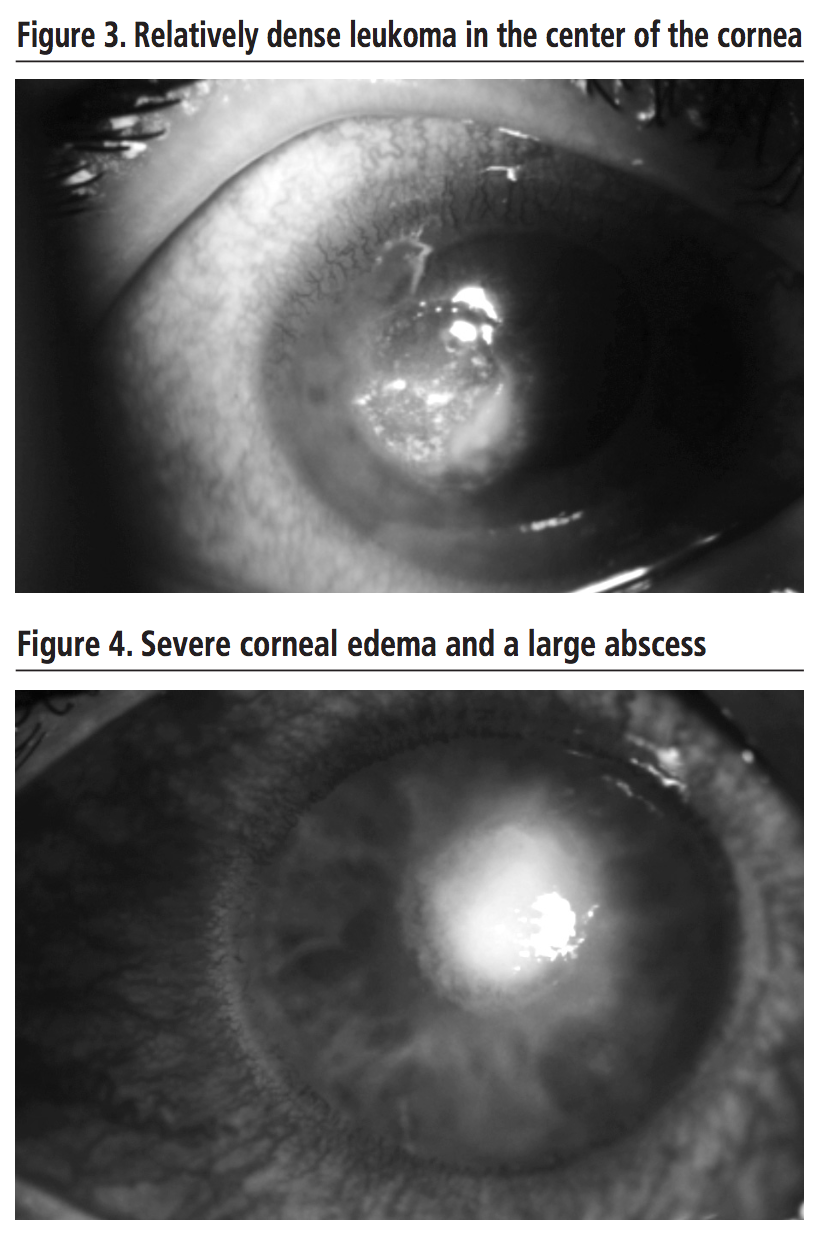

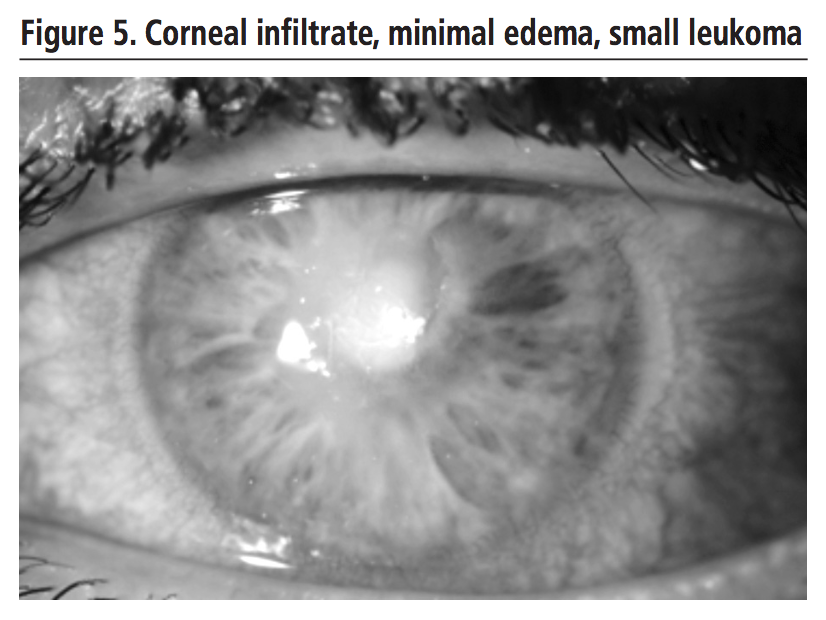

A 40-year-old male patient, with laser myopia surgery and contact lens wearer, was admitted due to outpatient treatment complications (ciprofloxacin 3 mg/ml, diclofenac 1 mg/ml). Upon admission, the patient presented a severe perilesional corneal edema and a large abscess in the cornea with a contracted pupil (Figure 4).  Large-spectrum antibiotic treatment with vancomycin and ceftazidime 50 mg/ml eye drops hourly was started and corneal sample was collected. On day 2, against the lack of improvement, and suspecting Acanthamoeba infection, antiparasitic treatment with propamidine 1 mg/ml was added, followed by the adition of topical natamycin 50 mg/ml one day later, as it looked like a filamentous fungus was growing in the culture. On day 8, the growth of Fusarium was confirmed, so it was decided to withdraw propamidine; voriconazole 10 mg/ml eye drops was added, to cover, along with natamycin, this entire fungal gender. 2 days later (day 10), patient was discharged with vancomycin and ceftazidim eye drops every 6 hours and natamycin and voriconazole every 2 hours, as well as adjuvant treatment with cyclopentolate, phenylephrine and dexamethasone eye drops. On the 32nd day, Fusarium solani was finally isolated in the culture; antibiotic eye drops were then discontinued, but it was decided to maintain both polyene and azol eye drops. On the 50th day, the patient was definitely discharged; he presented corneal infiltrate, minimal perilesional edema and a small leukoma (Figure 5).

Large-spectrum antibiotic treatment with vancomycin and ceftazidime 50 mg/ml eye drops hourly was started and corneal sample was collected. On day 2, against the lack of improvement, and suspecting Acanthamoeba infection, antiparasitic treatment with propamidine 1 mg/ml was added, followed by the adition of topical natamycin 50 mg/ml one day later, as it looked like a filamentous fungus was growing in the culture. On day 8, the growth of Fusarium was confirmed, so it was decided to withdraw propamidine; voriconazole 10 mg/ml eye drops was added, to cover, along with natamycin, this entire fungal gender. 2 days later (day 10), patient was discharged with vancomycin and ceftazidim eye drops every 6 hours and natamycin and voriconazole every 2 hours, as well as adjuvant treatment with cyclopentolate, phenylephrine and dexamethasone eye drops. On the 32nd day, Fusarium solani was finally isolated in the culture; antibiotic eye drops were then discontinued, but it was decided to maintain both polyene and azol eye drops. On the 50th day, the patient was definitely discharged; he presented corneal infiltrate, minimal perilesional edema and a small leukoma (Figure 5).

DISCUSSION

Fungal infections need to be promptly diagnosed. Treatment of infection with topical steroids is contraindicated, especially in the early stages, as they increase the proliferation and corneal penetration of the fungus5.

The azoles and polyenes family stand out among the available antifungal therapies. Voriconazole and amphotericin B are just some of the options, but is natamycin the one that stands out as the treatment of choice, especially in the case of filamentous fungi, such as Fusarium solani. It presents low corneal toxicity, but its action is limited by its limited corneal penetration. It is advisable to combine it with desbridations in order to improve its penetration1,2. The co-administration of natamycin and voriconazole increases the spectrum and even some studies suggest synergy, thus covering both filamentous and yeast infections4. Many of these eye drops, not available commercially, have to be prepared by the Pharmacy Service. Alternatively, they can be purchased through different foreign medication suppliers. If the infection is of major severity, systemic and/or intravitreous antifungal treatment of broad-spectrum drugs such as amphotericin B or voriconazole will be additionally administered2. Where pharmacological treatment is not sufficiently successful, surgical intervention such as lamellar keratoplasty will be considered2.

In the two reported cases, patients improved their clinical situation from the onset of treatment with topical natamycin and voriconazole, subsequently discontinuing voriconazole when Fusarium solani was confirmed as the etiological agent.

CONCLUSION

An early diagnosis in fungal infections is essential to implement antifungal treatment in the shortest possible time. Treatment of Fusarium solani corneal fungal infections with natamycin topical, both alone or in combination with voriconazole, is effective and safe. Clinical improvement and reduction of the ulcer was observed. However, other studies would be required to confirm the effectiveness of this treatment for this sort of conditions. Access to this medication in Spain is restricted because it is not commercially available. Entails a long and tedious process, which could delay the onset of the treatment and may lead to a poorer resolution of the patient’s clinic.The importance of the hospital pharmacist’s intervention is evidenced, both in the elaboration and in the acquisition of the amtimicrobial eye drops.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Pérez Díaz C, Barrios Castañeda P, Miranda Echevarría JD, Bravo Ojeda JS, Mantilla Flórez YF. Colección corneal intraestomal y queratitis por Fusarium spp: presentación de dos casos y revisión de la literatura. Revista Med. 2013; 21(2): 88-95.

2. Mellado F, Rojas T, Cumsille C. Queratitis fúngica: revisión actual sobre diagnóstico y tratamiento. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 2013;76(1):52-56.

3. Monzon A, Rodriguez Tudela JL. Infecciones causadas por el género Fusarium. Revision temática SEIMC [SEIMC]. Servicio de Micología. Centro Nacional de Microbiología. Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Majadahonda (Madrid); 2000 [quoted con 07 February 2018]. Available in: http://www.seimc.org/controldecalidadseimc.

4. UpToDate [Internet Database]. Nucci M, Anaissie E.: Treatment and prevention of Fusarium infection. [quoted on 27th December 2017]. Available in: http://www.uptodate.com.

5. Díaz Alemán VT, Perera Sanz D, Rodríguez Martín J, Abreu Reyes JA, Aguilar Estévez JJ, González de la Rosa MA. Arch Soc Canar Oftal. 2006;17:59-64.

____

Download PDF: Queratitis fúngica por Fusarium solani tratada con natamicina