Pousada-Fonseca A, Rubio Cebrián B, Morona-Minguez I, García-Martínez D, Mengual-Barroso R, Moriel Sánchez C.

Pharmacy Department, Hospital Universitario de Móstoles, Madrid, Spain

Fecha de recepción: 21/02/2023 – Fecha de aceptación: 21/03/2023

Correspondencia: Álvaro Pousada-Fonseca · Pharmacy Department, Hospital Universitario de Móstoles. Calle Doctor Luis Montes, S/N, 28935 Móstoles, Madrid (España) · alvaropousada@hotmail.com

___

Summary

Objectives: To validate the process of tablet splitting to obtain non-marketed doses prescribed in a university hospital in the Community of Madrid (Spain).

Material and methods: Using the information management system and the repackaging program products that were being split to get equivalent doses were located. Splitting information was obtained from technical data sheets and Botplus database. Drugs without supported dose-equivalent splitting whose characteristics did not contraindicate subdivision were selected. The mass uniformity test described in the European Pharmacopoeia and a mass loss test were performed to evaluate the equivalence of the doses obtained.

Results: Eighty-four doses obtained by splitting of 72 different drugs were identified. In 30 (41.7%) of the 72 drugs, there was no evidence to support divisibility into equivalent doses. Among these, 14 were identified as being suitable for assays to validate divisibility. Thirteen drugs (92.9%) (Edemox 250 mg, Trangorex 200 mg, Largactil 25 mg, Codeisan 28.7 mg, Masdil 60 mg, haloperidol Esteve 10 mg, Hydrapres 25 mg, Atarax 25 mg, Sinemet Plus 100 mg, lorazepam Normon 1 mg, metformina Sandoz 850 mg and Urbason 4 mg) met the requirements established in the mass uniformity test and in the mass loss test. Propranolol Accord 40 mg was the only drug that failed the assays.

Conclusions: Most of the tablets evaluated met the specifications to validate their use in our hospital. These results represent a solution for almost half of the drugs that were being split into equivalent doses and did not have evidence to support their division.

Keywords: Tablets, Pharmacy service, Hospital, administration and dosage, Pharmacopoeia, Drug compounding.

Validación del fraccionamiento de comprimidos para obtener dosis no comercializadas en un hospital.

Objetivos: Validar el fraccionamiento de formas farmacéuticas sólidas para obtener dosis no comercializadas en un hospital universitario de la comunidad de Madrid.

Material y métodos: Utilizando el maestro de artículos y el programa de reenvasado se localizaron los medicamentos que se fraccionaban para obtener mitades equivalentes. La información relativa al fraccionamiento se obtuvo de las fichas técnicas y Botplus. Se seleccionaron medicamentos sin fraccionamiento avalado cuyas características no contraindicasen la manipulación. Se realizaron el ensayo de uniformidad de masa descrito en la Farmacopea Europea y un ensayo de pérdida de masa.

Resultados: Se identificaron 84 dosis obtenidas por división de 72 fármacos. En 30 (41,7%) de los 72 fármacos no había bibliografía que apoyara la divisibilidad en dosis equivalentes. Entre estos, se identificaron 14 como aptos para realizar los ensayos de validación de la divisibilidad. Trece medicamentos (92,9%) (Edemox 250 mg, Trangorex 200 mg, Largactil 25 mg, Codeisan 28. 7 mg, Masdil 60 mg, haloperidol Esteve 10 mg, Hydrapres 25 mg, Atarax 25 mg, Sinemet Plus 100 mg, lorazepam Normon 1 mg, metformina Sandoz 850 mg y Urbason 4 mg) cumplieron los requisitos establecidos en los ensayos. Propranolol Accord 40 mg fue el único fármaco que no superó los criterios preespecificados.

Conclusiones: La mayoría de los comprimidos evaluados cumplieron las especificaciones para validar su uso en nuestro hospital. Estos resultados representan una solución para casi la mitad de los medicamentos que se estaban dividiendo en dosis equivalentes y no disponían de evidencia que avalara su división.

Palabras clave: Comprimidos, Servicio de Farmacia Hospitalaria, Dosis y administración, Farmacopea, Preparaciones farmacéuticas.

____

Introduction

When addressing the appropriateness of tablet splitting, regulatory agencies and Good Clinical Practice Guides generally advise against splitting unless this possibility is stated in technical data sheets (TDS) 1. The reason for this guideline is explained in the Spanish Good Practice Guideline for the Preparation of Medications in Hospital Pharmacy Services (SGPHP) as follows2:

“Tablet divisibility is a property that is assessed by the European Union regulatory agencies in accordance with the European Pharmacopoeia (EP) prior to granting marketing authorization for the medicinal product. Once evaluated, this property is included in the information on the drug’s package leaflet or in the TDS. Therefore, if such information is included, a tablet can be split.”

Despite these indications, there are situations in which the use of split dose drugs is a necessity that is difficult to address with other strategies. For example, there are often discrepancies between marketed doses and the doses used in clinical practice3. In addition, the increase in supply problems (1,643 recorded in 2021 in Spain4) encourages the use of this type of measure. In this regard, the SGPHP states that in the absence of available therapeutic alternatives on the market, the pharmacist in charge should assess the benefit/risk of splitting and provides general recommendations indicating those drugs that should not be split2 :

- Drugs under special medical control or with special safety measures (classification repealed from the Spanish Law in December 20195).

- Drugs with active ingredients with a narrow therapeutic index according to Spanish Law6.

- Modified-release tablets (prolonged, pulsatile or delayed release, including gastroresistant ones).

- Drugs for buccal use or oral lyophilized.

Therefore, when appropriate, it is the pharmacist’s responsibility to evaluate the convenience of this divisibility. In this sense, replicating the assays established in the EP to validate the use of split tablets seems reasonable. In the monograph corresponding to tablets, it is stated that the score line can be used to facilitate administration or to subdivide the tablet into equivalent doses7. In the latter case, the need to evaluate the effectiveness of the score line to ensure the mass uniformity of the fractions obtained is established, indicating the test to be carried out (mass uniformity test) 7,8. The American Pharmacopoeia (AP) establishes similar parameters to the European ones9 and, in addition, up to its 29th edition it included as a requirement a maximum relative standard deviation (RSD) of 6% for each fraction10. Beyond the official recommendations, some authors have proposed complementary tests (mass loss test and split facility) to validate the divisibility process11,12.

The objective of this study is to validate the process of tablet splitting to obtain non-marketed doses prescribed in our hospital.

Material and methods

The review and testing were conducted between May 2021 and November 2022. Using the information management system and the hospital’s repackaging program, the drugs that were being split in the Pharmacy Service to achieve the prescribed doses were located. Using the Botplus database, the information on tablet splitting was located and compared with the TDS (the latter prevailing in the event of discrepancies).

Using Microsoft Excel 2013, a database of splitting tablets was created in which the following variables were collected: Active ingredient and dose, National Code (NC), commercial brand, available alternative of the target dose (Yes/No), possibility of splitting into equivalent doses available in TDS (Yes/No), possibility of splitting to facilitate swallowing in TDS (Yes/No), modified release (Yes/No), presence of a score line (Yes/No), ability to be administrated by enteral tube according to Medisonda guide (Yes/No) and drug with a narrow therapeutic index according to Spanish Law (Yes/No).

Drugs for which the subdivision into equivalent doses was contemplated in the TDS, those for which marketed solid dosage forms were available at the dose sought, and drugs with a narrow therapeutic index were discarded. Among the remaining drugs, only non-enteric-coated, immediate-release tablets with a score line that met at least one of the following characteristics were selected:

- The TDS includes the possibility of splitting the tablet to facilitate swallowing.

- Medications that can be manipulated for enteral tube administration in accordance with the Medisonda Enteral Tube Medication Administration Guide.

The following assays were carried out with the drugs that met the inclusion criteria:

Mass uniformity test adapted from EP7:

Take 30 tablets at random, break them and from all the parts obtained from 1 tablet, take 1 part for the test, and reject the other part(s). Weigh each of the 30 parts individually and calculate the average mass. The tablets comply with the test if not more than 1 individual mass is outside the limits of 85 per cent to 115 per cent of the average mass. The tablets fail to comply with the test if more than 1 individual mass is outside these limits, or if 1 individual mass is outside the limits of 75 per cent to 125 per cent of the average mass.

Mass loss test described by Green et al.11:

Take 30 tablets at random. Weigh each tablet. Break each tablet, and weigh each of the subdivided parts. Calculate the loss of mass for that tablet. Repeat the procedure for the other 29 tablets and calculate the mean loss of mass. Criterion for Loss of Mass: The tablets comply with the test if the mean loss of mass is not more than 1%.

RSD calculation:

To split the tablets, the pharmacists included in the study used one of the splitting devices available in the Pharmacy Service.

Two precision balances were used to weigh the tablets and fractions:

- Ohaus Scout model SKX123 with a maximum weight of 120 g and d=0.001 g.

- Sartorius model B310S with a maximum weight of 310 g and d= 0.001g.

Microsoft Excel 2013 was used to perform calculations.

Tablets were determined to be suitable for obtaining equivalent doses if they met the requirements stipulated in the uniformity and mass loss tests. The RSD was calculated as a measure of splitting variability, but no cut-off point was established that would condition the validity of the process.

Results

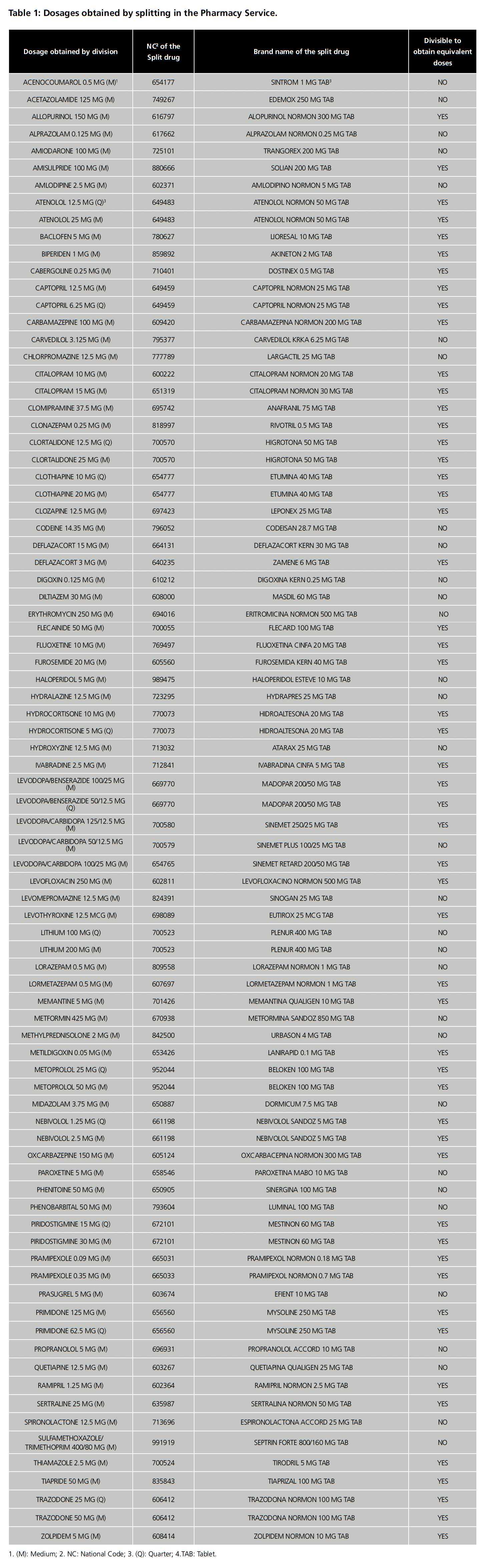

Seventy-two different drugs were identified as being split in the Pharmacy Service (table 1). Forty-two (58.3%) were excluded because obtaining equivalent doses was contemplated in the TDS, 3 (4.2%) because there were marketed alternatives to the dose sought (erythromycin 250 mg, prasugrel 5 mg and sulfamethoxazole/trimethoprim 400/80 mg) and 2 because they have a narrow therapeutic index (digoxin and phenytoin) (2.8%).

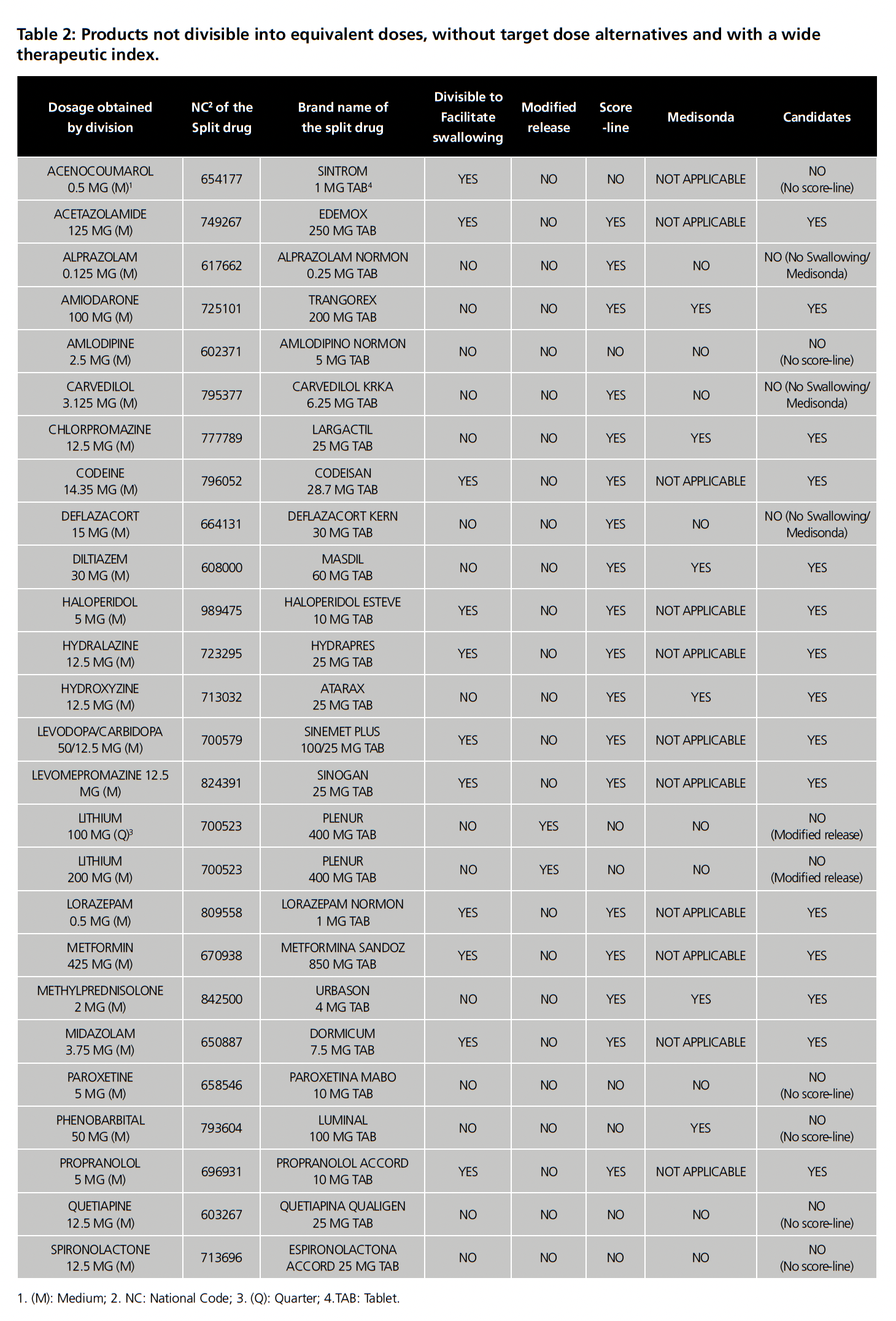

Among the remaining 25 drugs, 11 (44%) were found in which the TDS included the possibility of splitting to facilitate swallowing. Of these, 1 (Sintrom) was excluded because it did not have a score line. Of the 14 drugs without specific recommendations for splitting to facilitate swallowing, 8 drugs were identified that did not have an enteric coating, had a score line and were immediate release but only 5 drugs had data on administration by enteral tube in the Medisonda Guide. In total, 15 drugs met the requirements for uniformity and mass loss tests (table 2). Due to the shortage of Dormicum 7.5 mg, the study was carried out with 14 drugs, which are listed with their respective batches in table 3.

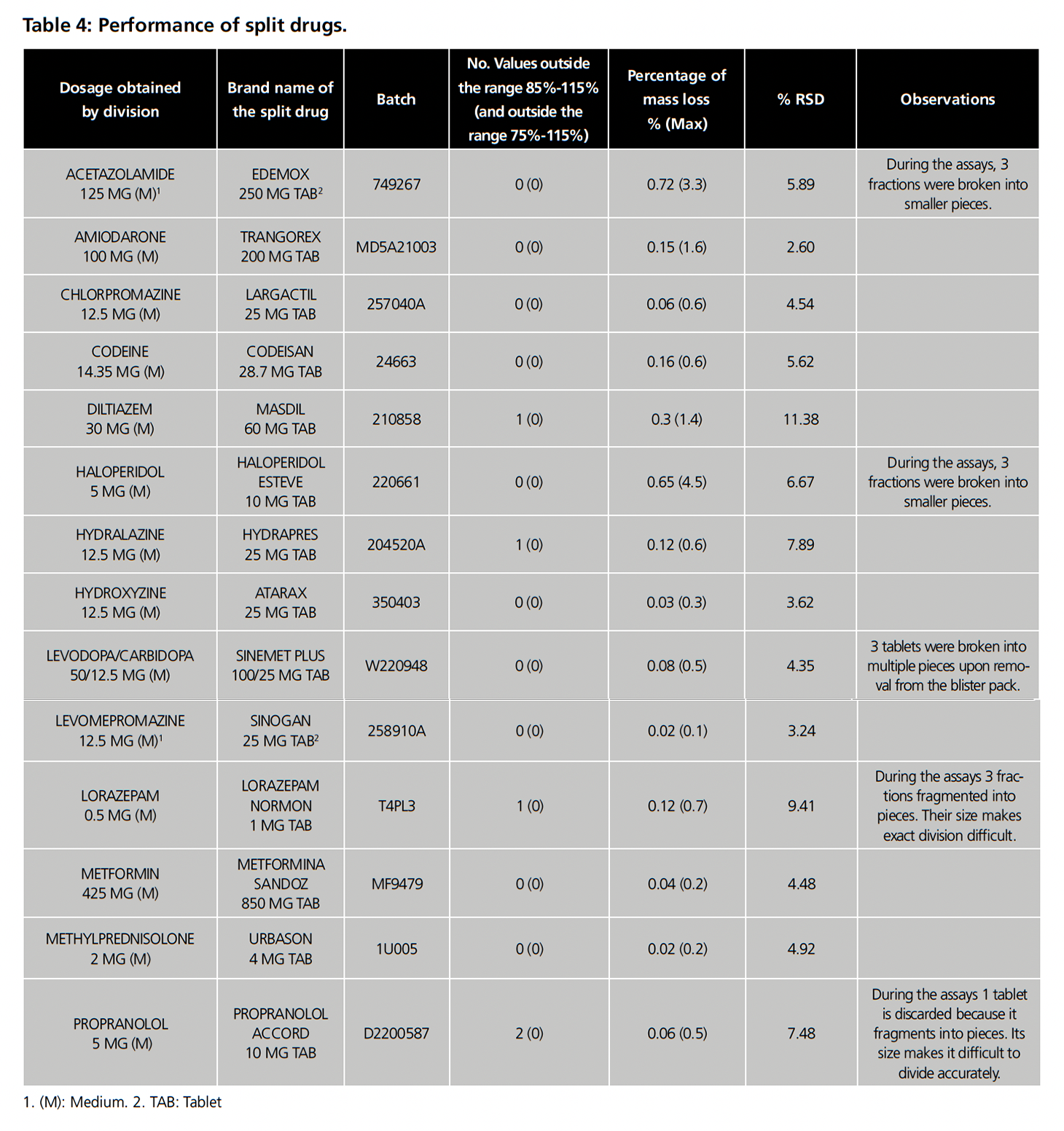

Table 4 summarizes the performance of the products evaluated. Of the 14 products, only 1 (7.1%) failed the mass uniformity test (propranolol Accord 5 mg), while the splitting of the remaining drugs produced no more than one fraction with masses outside the target range of 85% to 115% and therefore passed the test. Three products (21.4%) (lorazepam Normon 1 mg, Hydrapres 25 mg and Masdil 60 mg) had a fraction outside the target range, but none crossed 75% or 125%. In general, the tablets did not crumble, as evidenced by the fact that 100% passed the mass loss test, with no products exceeding a 1% loss. However, during the tests, Edemox 250 mg, haloperidol Esteve 10 mg, Sinemet plus 100 mg/25 mg, lorazepam Normon 1 mg and propranolol Accord 5 mg presented at least one tablet or fraction with integrity problems during handling as shown in the observations in table 4. Regarding RSD, 9 drugs were below 6%, 4 presented a value between 6 and 10% and only 1 (Masdil 60 mg) exceeded 10%.

In summary, 13 of the 14 drugs (92.9%) passed the tests which validate the obtaining of equivalent halves, which was a solution for 43.3% of the 30 drugs that did not have evidence to support their division into equivalent doses (table 1).

Discussion

The results obtained in this study show that the majority (92.9%) of the drugs (whose characteristics do not contraindicate splitting) that were being divided in our hospital meet the requirements established in the EP to be divided into equivalent doses. This performance is substantially superior to those obtained in similar publications, which show a great variability among the results obtained. Similar studies have been published since the 1980s in which the equivalence of split drugs has been evaluated by assessing the mass uniformity of the halves obtained. Among the publications that have shown more modest performances are those published by Teng et al. and Tahaineh et al. in which only 18.2% and 25% of the evaluated products passed the mass uniformity tests to which they were subjected13,14. Their results were consistent with previous studies such as those carried out by Gupta et al. in 1988 where only one of the five products evaluated was within the preset margin of 20% 15 or that published by Stimpel et al. which concluded that only 17% of the drugs evaluated are “excellent for division into equivalent doses”16. As for studies with more favorable results, Polli et al. evaluated the mass uniformity of 12 split drugs and 66.7% of them met the adapted standards of the AP17. A precedent study that did exceed 40% was carried out by the research of Sedrati et al. in which 7 of the 15 products evaluated had less than a fraction exceeding 15% with respect to the mean mass of the product18.

More recently, some research has used not only mass uniformity as an assessment measure but also content uniformity when evaluating the equivalence of split drugs. These studies are uncommon, possibly due to the greater ease of access to a precision balance than to a spectrophotometer or HPLC. In this regard, in 2015 in a study conducted in Egypt, in which the mass and content uniformity (with spectrophotometer) of the fractions of 16 commonly used drugs were evaluated, 62.5% of the products met the pre-specified standards (based on AP specifications). In this study, a perfect correlation was observed between those products that met the mass and content specifications and those that did not19. In a similar study Hill et al. obtained positive results for 50% of the products evaluated for mass uniformity and the same results for content uniformity (measured by HPLC) after mass adjustment20.

The wide variability between studies may be due to several factors. Firstly, the assays used to validate division differ from one study to another. In our case, we used the requirements established in the European and Spanish pharmacopoeias and additionally added the mass loss assay described by Green et al.11 The majority of the other articles are based on adaptations of tests collected in the AP13,14,17,19,20, which until its 29th edition included as a requirement a maximum RSD of 6% for each fraction (although in many of the aforementioned studies the range is extended to a maximum of 10%). In this sense, if we had taken this condition into account, our yields would be 64.3% (for a maximum RSD of 6%) or 85.7% (for a maximum RSD of 10%). Another factor that may influence the disparity of results is the selected method to split tablets (by hand, splitting device, knife, etc.). For our study, we selected the use of a splitting device for several reasons. Firstly, it is the tool used by pharmacy technicians at our hospital to split tablets. In addition, several previous studies have pointed out the advantages of this method over the alternatives20,21. This may be an important difference from studies such as that of Gupta et al. in which the tablets were broken by hand15. A third factor that may have an impact on the variability of results is the selection of the drugs tested. Many of the studies did not make a specific selection of the drugs to be split, but in general mention products “that are usually split”, and include drugs that were excluded from our research, such as medications with a narrow therapeutic index or those that have no score lines13–15,19,20. In our case, we selected scored tablets that met the SGPHP recommendations.

Regarding our findings, in a previous study, we presented the results obtained in the search for alternatives after evaluating and identifying split drugs in our hospital (table 1) in which divisibility to obtain equivalent doses was not recommended in the TDS or by the laboratory. Despite achieving a reduction in inappropriate splitting of 23.4%, the percentage of unsupported division remained above 10%22. These results showed that the search for marketed alternatives and compounding are only partially effective in the difficulty of obtaining the prescribed doses. For this reason, the ability to validate the obtaining of equivalent fractions in 13 of the 14 drugs tested represents an alternative strategy to obtain the prescribed doses. Regarding the limitations of our research, we can highlight the uncertainty in selecting the drugs that are truly candidates for validating division into equivalent doses. Following the SGPHP guidelines, we selected drugs that did not belong to the narrow therapeutic index category and that were of immediate release (discarding those of prolonged, pulsatile or delayed release, including gastroresistant drugs, and those for buccal use or oral lyophilized). In addition, for greater safety, we decided to work only with those products in which TDS guaranteed that they could be manipulated to facilitate swallowing or in which the Medisonda Guide included their use, assuming these indications implied that manipulating the integrity of the tablet did not compromise their bioavailability. Due to the limited literature available and the lack of validated standards, it is difficult to know whether this selection is restrictive or lax.

On the other hand, it is important to keep in mind that tablet handling could be associated with significant variation in stability. For example, although we ruled out enteric-coated drugs, some of the products we split were film-coated and we cannot be certain in what cases the coating plays a role in stability. Although not much has been written on this subject, some authors have used mass loss to evaluate deliquescence after two weeks of storage without observing significant differences23. Other study has used HPLC to evaluate the potency of different brands of split gabapentin, establishing that all the products evaluated were stable after nine weeks of storage24. Margiocco et al. evaluated the 30-day stability (by spectrophotometry or HPLC) of drugs used in cardiology, found statistically significant losses of content for several active ingredients, although probably not clinically relevant except in the case of digoxin25. At our hospital, split tablets are repackaged with a six-month shelf life.

Another aspect to consider is that, despite the high percentage of drugs that passed the established tests, 30.8% of the drugs presented at least one tablet or fraction with integrity problems during handling, which could raise doubts about the reproducibility of the test. In this sense, one possibility would be to carry out quality control periodically, to evaluate that the tablets meet the established requirements when the process is replicated. In any case, it is essential to perform a visual quality control prior to the repackaging of the medication, to ensure the integrity of the fractions to be dispensed.

Finally, all the tests performed exclusively validate the commercial brand with which the tests were performed. For this reason, a hypothetical change of commercial brand will imply the performance of new assays.

Conclusions

Most of the tablets evaluated complied with the pre-established specifications to validate their use in our hospital. These results represent a solution with guarantees for almost half of the drugs that were being split and for which there was no evidence supporting their division into equivalent doses. The use of these split drugs should always be accompanied by visual quality control to avoid repackaging crumbling fractions. Further work is needed to evaluate the possibility of expanding the drugs that are candidates for this type of assay when there are no alternatives on the market.

The authors declare no conflict of interest

Bibliography

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Best Practices for Tablet Splitting [online]. 2013. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/ensuring-safe-use-medicine/best-practices-tablet-splitting (accessed 25 Oct 2022).

- Casaus Lara ME, Tarno Fernández ML, Martín de Rosales Cabrera AM, et al. Guía de Buenas Prácticas de Preparación de Medicamentos en Servicios de Farmacia Hospitalaria [online]. 2014. https://www.sefh.es/sefhpdfs/GuiaBPP_JUNIO_2014_VF.pdf (accessed 26 Oct 2022).

- Cohen JS. Tablet splitting: imperfect perhaps, but better than excessive dosing. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2002; 42(2):160–2. doi: 10.1331/108658002763508443.

- Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios. Informe semestral sobre problemas de suministro. Enero-junio 2022 [online]. 2022. https://www.aemps.gob.es/medicamentosUsoHumano/problemasSuministro/informes-semestrales/docs/primer-informe-semestral-2022.pdf (accessed 26 Oct 2022).

- Real Decreto 717/2019, de 5 de diciembre, por el que se modifica el Real Decreto 1345/2007, de 11 de octubre, por el que se regula el proceso de autorización, registro y condiciones de dispensación de los medicamentos de uso humano fabricados industrialmente [online]. 2019. https://www.boe.es/diario_boe/txt.php?id=BOE-A-2019-17611 (accessed 26 Oct 2022).

- Orden SCO/2874/2007, de 28 de septiembre, por la que se establecen los medicamentos que constituyen excepción a la posible sustitución por el farmacéutico con arreglo al artículo 86.4 de la Ley 29/2006, de 26 de julio, de garantías y uso racional de los medicamentos y productos sanitarios [online]. 2007. https://www.boe.es/eli/es/o/2007/09/28/sco2874/con (accessed 30 Oct 2022).

- European Directorate for the Quality of Medicines and Healthcare. European Pharmacopoeia [online]. 2020. http://www.uspbpep.com/ep60/tablets%200478e.pdf (accessed 27 Oct 2022).

- Real Farmacopea Española en Internet [online]. 2022. https://extranet.boe.es/farmacopea/ (accessed 26 Oct 2022).

- United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary, USP44-NF39. Chapter 905: Uniformity of dosage units [online]. 2021. https://online.uspnf.com/uspnf/document/1_GUID-BA3755E4-77AA-4DEB-8FE2-4FC78C587E9E_1_en-US (accessed 27 Dec 2022).

- United States Pharmacopeia and National Formulary, USP29-NF24. Chapter 905: Uniformity of dosage units [online]. 2006. http://ftp.uspbpep.com/ (accessed 27 Dec 2022).

- Green G, Berg C, Polli JE, et al. Pharmacopeial standards for the subdivision characteristics of scored tablets. Pharm Forum 2009;35(6):1598–1612. doi: 10.13140/2.1.4057.6807

- van Santen E, Barends DM, Frijlink HW. Breaking of scored tablets: A review. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2002;53(2):139–45. doi: 10.1016/s0939-6411(01)00228-4

- Teng J, Song CK, Williams RL, et al. Lack of medication dose uniformity in commonly split tablets. J Am Pharm Assoc (Wash) 2002;42(2):195–9. doi: 10.1331/108658002763508489

- Tahaineh LM, Gharaibeh SF. Tablet splitting and weight uniformity of half-tablets of 4 medications in pharmacy practice. J Pharm Pract 2012;25(4):471–6. doi: 10.1177/0897190012442716

- Gupta P, Gupta K. Broken tablets: does the sum of the parts equal the whole? Am J Hosp Pharm 1988;45(7):1498. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/45.7.1498.

- Stimpel M, Küffer B, Groth H, et al. Breaking tablets in half. Lancet 1984;1(8389):1299. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(84)92481-4

- Polli JE, Kim S, Martin BR. Weight uniformity of split tablets required by a Veterans Affairs policy. J Manag Care Pharm 2003;9(5):401–7. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2003.9.5.401

- Sedrati M, Arnaud P, Fontan JE, et al. Splitting tablets in half. Am J Hosp Pharm 1994;51(4): 548-9. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/51.4.548

- Helmy SA. Tablet Splitting: Is It Worthwhile? Analysis of Drug Content and Weight Uniformity for Half Tablets of 16 Commonly Used Medications in the Outpatient Setting. J Manag Care Spec Pharm 2015;21(1):76–86. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2015.21.1.76

- Hill SW, Varker AS, Karlage K, et al. Analysis of drug content and weight uniformity for half-tablets of 6 commonly split medications. J Manag Care Pharm 2009;15(3):253–61. doi: 10.18553/jmcp.2009.15.3.253

- Habib WA, Alanizi AS, Abdelhamid MM, et al. Accuracy of tablet splitting: Comparison study between hand splitting and tablet cutter. Saudi Pharm J 2014;22(5):454-9. doi: 10.1016/j.jsps.2013.12.014

- Pousada-Fonseca A, Rubio Cebrian B, Soto-Baselga I, et al. Evaluación de la divisibilidad de formas farmacéuticas sólidas para optimizar la dispensación [First Online]. Rev. OFIL·ILAPHAR. 2022. https://www.ilaphar.org/evaluacion-de-la-divisibilidad-de-formas-farmaceuticas-solidas-para-optimizar-la-dispensacion/

- Boggie DT, DeLattre ML, Schaefer MG, et al. Accuracy of splitting unscored valdecoxib tablets. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2004;61(14):1482–3. doi: 10.1093/ajhp/61.14.1482

- Volpe DA, Gupta A, Ciavarella AB, et al. Comparison of the stability of split and intact gabapentin tablets. Int J Pharm 2008; 350(1–2):65–9. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2007.08.041

- Margiocco ML, Warren J, Borgarelli M, et al. Analysis of weight uniformity, content uniformity and 30-day stability in halves and quarters of routinely prescribed cardiovascular medications. J Vet Cardiol 2009;11(1):31–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jvc.2009.04.003