Marco Garbayo JL, Koninckx Cañada M, Pérez Castelló I, Faus Soler MT, Bourgon Baquedano L, Pérez Mahiques R

Servicio de Farmacia. Hospital Francesc de Borja. Gandia. Valencia (España)

Fecha de recepción: 31/08/2018 – Fecha de aceptación: 20/09/2018

Correspondencia

Manuel Koninckx Cañada – Avda. de la Medicina, 6 – 46702 Gandia, Valencia (España)

koninchk_man@gva.es

____

Summary

Objectives: To assess the prevalence, preventability and outcomes of drug-related hospitalisations. To describe the drug-related problems (DRPs) and the medications involved.

Methods: An observational retrospective cohort study was conducted in the framework of an integral risk management plan of drugs and proactive pharmacovigilance of drug-related hospitalisations occurring from January 1 to December 31, 2017. Cases were identified using the information management tool of Orion Clinic (hospital electronic medical history) and by reviewing the hospital discharge reports. A descriptive analysis of demographic, clinical, and drug-related variables was conducted. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.19.0.

Results: Overall, 395 out of 8,364 hospital admissions (4.7%, 95% CI 4.3 to 5.2) were due to DRPs. The median (IQR) length of stay was 4.0 (2.0-6.0) days. A total of 412 DRPs were detected, being digestive disorders (102 cases, 24.8%), endocrine disorders (70 cases, 17.0%) and blood disorders (64 cases, 15.5%) the most frequent. Antithrombotic, antineoplastic, cardiovascular and antidiabetic drugs were most common groups and were involved in 89 (21.6%), 78 (18.9%), 69 (16.7%) and 49 (11.9%) DRPs, respectively. Ninety-two DRPs (22.3%) were considered preventable, being the most frequent those related with omission of dose/medication (26 cases, 6.3%) and nonadherence (23 cases, 5.6%). Nineteen patients (5.0%) died during the admission, ten of whom (52.6%) due to DRPs.

Conclusions: Drug-related hospitalisations is a current and significant problem, being preventable a not negligible percentage of them. Feedback of our results, together with multidisciplinary educational strategies, can help to improve the safe use of medicines.

Key Words: Adverse drug event, adverse drug reaction, drug-related problem, electronic data processing, hospitalisation, medication errors, pharmacovigilance, safety.

____

Prevalencia, evitabilidad y resultados de los ingresos hospitalarios relacionados con medicamentos: datos anuales de un plan integral de gestión de riesgos con medicamentos y farmacovigilancia proactiva

Resumen

Objetivos: Evaluar la prevalencia, evitabilidad y resultados de los ingresos hospitalarios por medicamentos. Describir los problemas relacionados con los medicamentos (PRMs) y los fármacos involucrados.

Métodos: Estudio de cohortes observacional retrospectivo realizado en el marco de un plan integral de gestión de riesgos con medicamentos y farmacovigilancia proactiva de los ingresos hospitalarios por medicamentos ocurridos durante el año 2017. Los casos se identificaron utilizando la herramienta de gestión de la información de Orion Clinic (historia clínica electrónica hospitalaria) y revisando los informes de alta. Se realizó un análisis descriptivo de las variables demográficas, clínicas y relacionadas con los tratamientos. El análisis estadístico se realizó con SPSS V.19.0.

Resultados: 395 de 8.364 ingresos hospitalarios (4,7%, IC 95% de 4,3 a 5,2) se debieron a PRMs. La mediana (RIQ) de la estadía hospitalaria fue de 4,0 (2,0-6,0) días. Se detectaron un total de 412 PRMs, siendo los trastornos digestivos (102 casos, 24,8%), trastornos endocrinos (70 casos, 17,0%) y trastornos sanguíneos (64 casos, 15,5%) los más frecuentes. Los fármacos antitrombóticos, antineoplásicos, cardiovasculares y antidiabéticos fueron los grupos más comunes y estuvieron presentes en 89 (21,6%), 78 (18,9%), 69 (16,7%) y 49 (11,9%) PRMs, respectivamente. Noventa y dos PRMs (22,3%) se consideraron prevenibles, siendo los más frecuentes los relacionados con la omisión de dosis/medicación (26 casos, 6,3%) y la falta de adherencia (23 casos, 5,6%). Diecinueve pacientes (5,0%) murieron durante el ingreso, diez de ellos (52,6%) debido al PRM.

Conclusiones: Los ingresos hospitalarios relacionados con los medicamentos es un problema actual y significativo, pudiéndose evitar un porcentaje no despreciable de ellos. La retroalimentación de nuestros resultados, junto con estrategias educativas multidisciplinares, puede ayudar a mejorar el uso seguro de los medicamentos.

Palabras clave: Evento adverso a medicamentos, reacciones adversas a medicamentos, problemas relacionados con medicamentos, procesamiento electrónico de datos, hospitalización, errores de medicación, farmacovigilancia, seguridad.

____

Introduction

Drugs are prescribed to achieve an optimal pharmacotherapeutic goal, but its use is indisputably linked to safety outcomes. Since the 1960s and after publication of several studies1-3, but mainly following the report of the Institute of Medicine “To err is human: Building a Safer Health System”4, the impact of harmful events associated with the clinical use of drugs has been known.

Adverse drug events (ADEs), adverse drug reactions (ADRs) and medication errors (MEs) are used as terms in scientific publications on patient safety, but they can be grouped under the concept of drug-related problems (DRPs)5,6. In any case, analysis of those events that are severe and, therefore, cause hospitalisation is especially important. International data revealed that around 5-10% of hospital admissions are drug-related6-8.

In hospital practice, several methods are used to detect and quantify DRPs5. The voluntary registration and reporting systems are the most internationally widespread, but they are associated with significant underreporting, so their effectiveness is low. Therefore, proactive methodologies should be considered. The information technologies and management of integrated data in the healthcare Electronic Information Systems (EIS) play a key role in this proactivity.

The aim of this study was to analyse the prevalence, preventability and outcomes of hospital admissions resulting from DRPs at the Health Department of Gandia, Valencia, Spain.

Methods

Study design and data source

An observational retrospective cohort study of drug-related hospitalisations at the Health Department of Gandia was conducted for a one-year period (from January 1 to December 31, 2017). This study was developed in the context of an integral risk management plan of drugs and proactive pharmacovigilance.

Data were collected from the corporate EIS Abucasis (the ambulatory medical history), Alumbra (the business intelligence that works on the data warehouse that integrates information of electronic prescriptions), Farmasyst (the pharmacotherapeutic history) and Orion Clinic (the hospital electronic medical history).

Study population

The population assigned to our Health Department and to our hospital is around 166,800 inhabitants. Cases were detected systematically and retrospectively by using the information management tool of Orion Clinic. The date range from 01/01/2017 to 12/31/2017 and the medical departments of Haematology, Intensive Care, Internal Medicine, Paediatric, Psychiatry and Short Stay were used as search filter on the hospital discharge reports. Departments of General Surgery, Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Ophthalmology, Orthopaedic and Traumatology Surgery, Otorhinolaryngology and Urology were not included.

All generated cases were assessed by the pharmacist team participating in the integral risk management plan of drugs and proactive pharmacovigilance, of whom drug-related hospital admissions were included in the analysis. The medical criteria, set out explicitly in the same discharge reports, were considered as sufficient for acceptance of accountability. However, by using the Naranjo adverse drug reaction probability9, it was confirmed that the detected cases had at least a probable causal relationship. Patients admitted due to intentional poisonings and cases without relevant information for the analysis were excluded.

Study variables

Information about sex, age, main pathology, relevant medical history, laboratory and diagnostic tests, evolution during admission and ongoing medication (generic name and number of days of treatment) was collected. The Clinical Risk Group (CRG) core health status of patients was also collected10. International Classification of Diseases, Tenth revision (ICD-10), was used for coding the detected DRPs and their preventability was assessed using the Schumock and Thorton questionnaire11. When DRPs proved to be preventable, the Spanish Taxonomy of the Ruiz-Jarabo Group 2000 was used to categorise the MEs associated with them12.

Drugs were encoded according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) index. Treatment was imputed as self-medication when the definition proposed by Asseray et al was met13. Exposure to treatment was defined adapting the model used by Lewis et al.14: “short-term”, when the drug was taken on admission and in the previous week, but not before that; “long-term”, when the drug was taken on admission and for more than one week before that; “recent”, when the drug was not taken on admission, but in the week before that; and “not recent”, when the drug was not taken on admission nor during the week before that.

Statistical analyses

Continuous variables were reported as median and interquartile range (IQR). Relative and absolute frequencies were used for categorical variables. Differences between groups in patient characteristics were analysed using Mann-Whitney U test and χ2 tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Prevalence rates of drug-related hospitalisations, with 95% confidence intervals (CIs), were also calculated. All tests were two-sided with a statistical confidence level of 95% and were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 19.0 (Armonk, NY).

Ethical issues

This healthcare quality program was approved by the Teaching, Investigation and Ethics Commission of Gandia Health Department. Also, it is integrated in research projects managed by the Foundation for the Promotion of Health and Biomedical Research of Valencia (ref. FISABIO 2015/31).

Results

Over one year, a total of 14,099 admissions occurred in the hospital. The study included 8,364 hospitalisations to the medical departments under consideration, 395 of which (4.7%, 95% CI 4.3 to 5.2) were associated with at least one DRP. The prevalence in paediatric patients (aged ≤14 years) was 1.5% (95% CI 0.6 to 2.4), whereas in the elderly (aged ≥65 years) it was 5.2% (95% CI 4.6 to 5.8).

Characteristics of patients

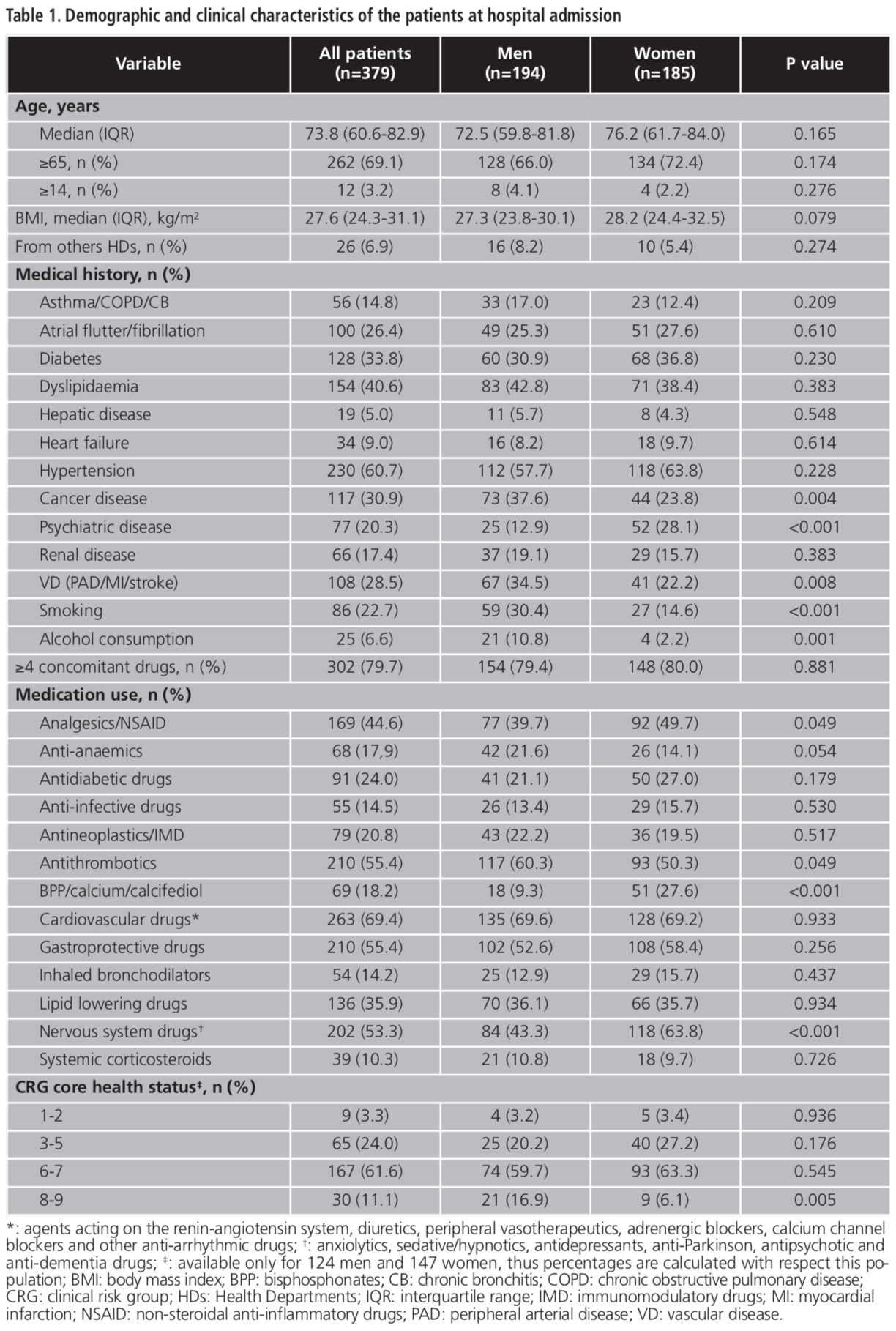

The study population (379 patients) was distributed according to the sex: 194 (51.2%) were men and 185 (48.8%) were women. Fourteen patients and one patient had two and three hospital admissions due to DRPs, respectively. Table 1 shows the demographic and clinical characteristics according to sex.

Types of drug-related problems

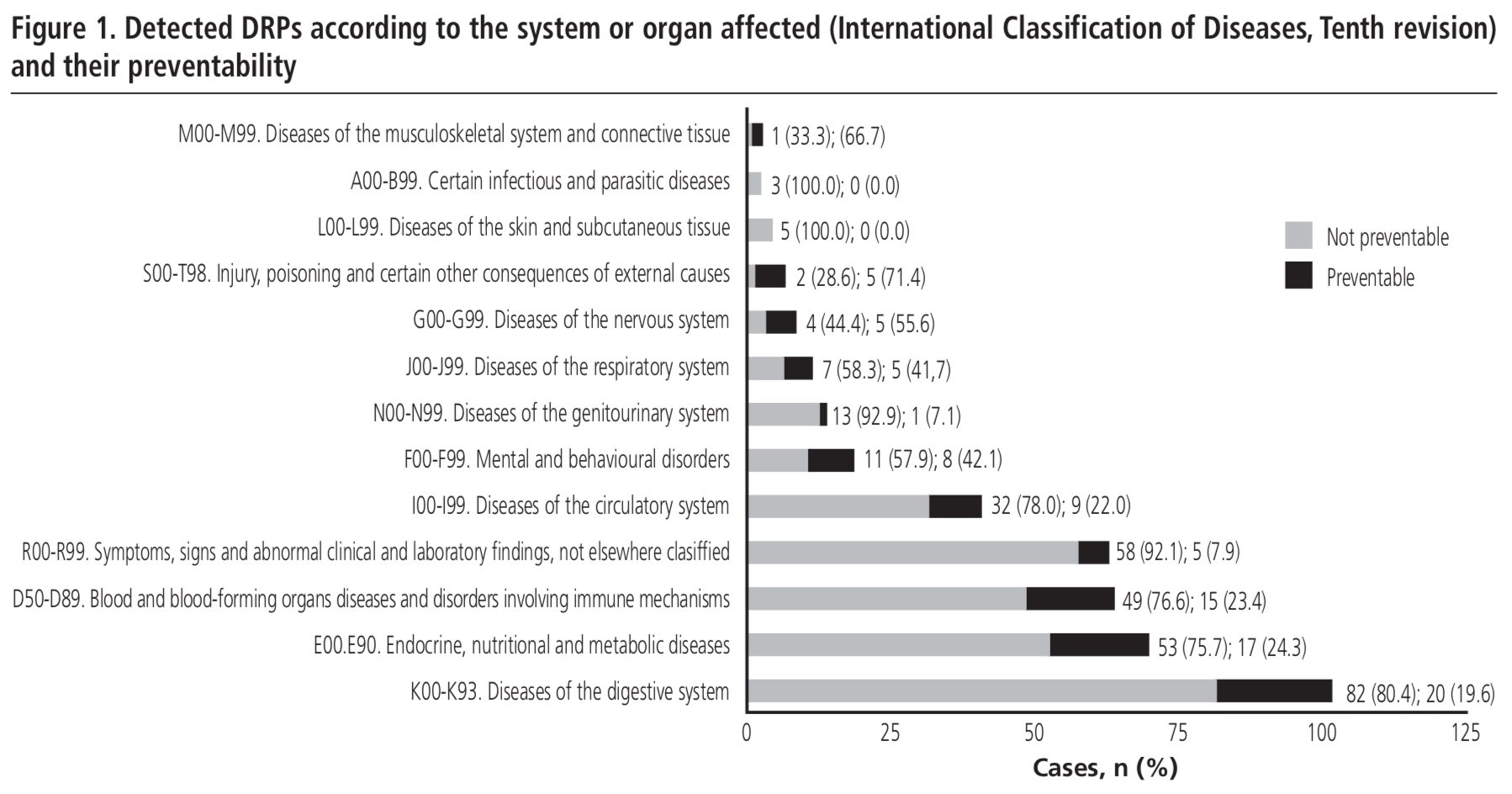

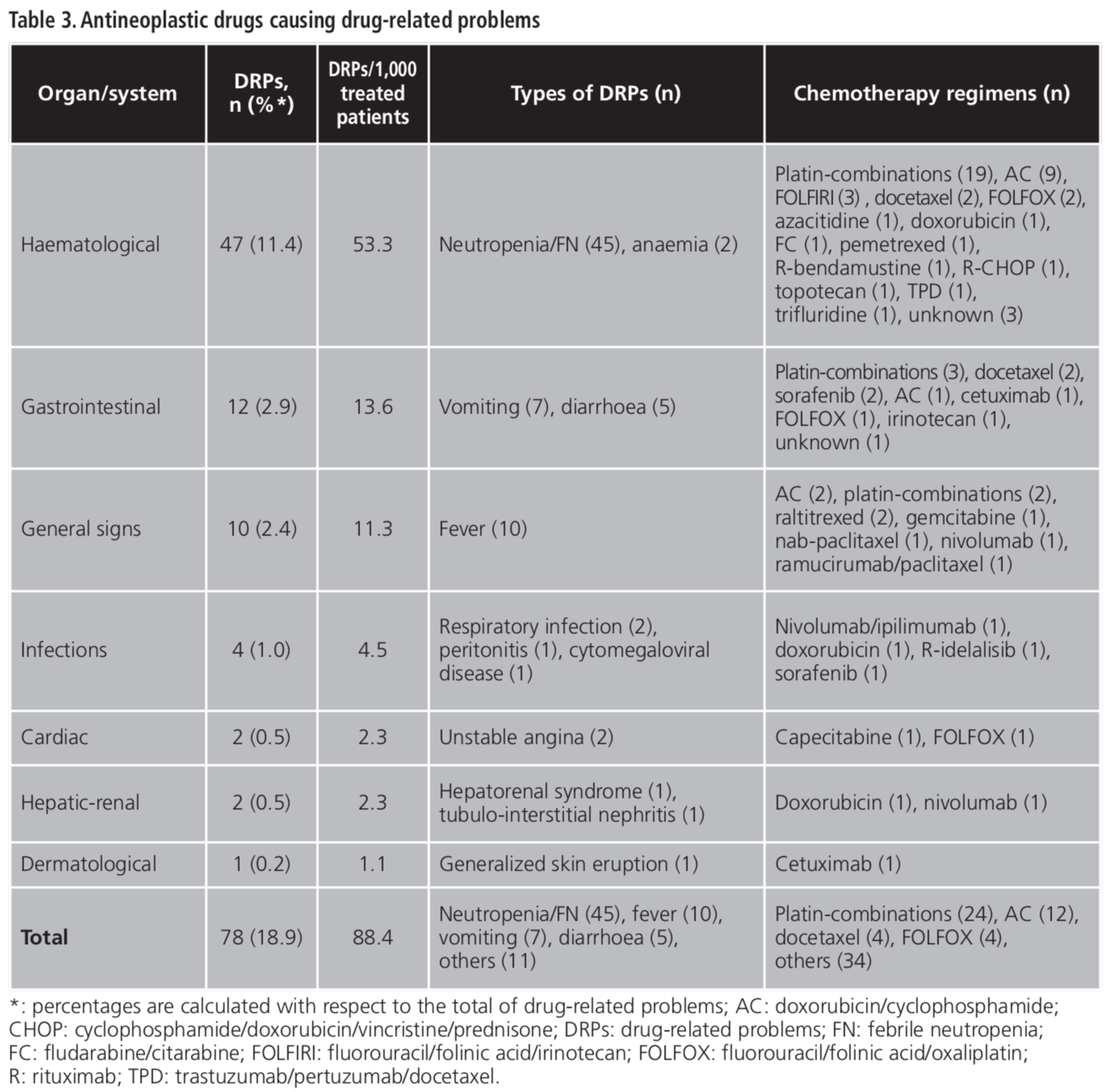

A total of 412 DRPs were detected, 388 of which (94.2%) were directly responsible for the admission (attributed as primary diagnosis), while 24 (5.8%) were identified during the admission (attributed as secondary diagnosis). Figure 1 groups the DRPs according to the ICD-10 and their preventability. Ninety-two DRPs (22.3%) were classified as preventable, while 320 (77.7%) were not preventable. A higher proportion of DRPs affected the digestive system (102 cases, 24.8%), the endocrine system (70 cases, 17.0%) and the blood system (64 cases, 15.5%). The most frequent cause of hospital admission was gastrointestinal bleeding (74 cases, 20.0%), followed by neutropenia (45 cases, 10.9%) (Table 2 and Table 3).

Suspected drugs, type of exposure and actions taken

A total of 509 individual or combined drugs were associated with the detected DRPs. According to the type of exposure, 325 treatments (63.9%) were classified as “long-term” use, 74 (14.5%) as “not recent” use, 55 (10.8%) as “short-term” use and 55 (10.8%) as “recent” use. Forty-nine DRPs (11.9%) were directly related to self-medication.

Table 2 and Table 3 list the drugs causing DRPs. The four most frequent classes were antithrombotics (89 cases, 21.6%), antineoplastics (78 cases, 18.9%), cardiovascular drugs (69 cases, 16.7%) and antidiabetics (49 cases, 11.9%). The groups with higher ratio per 1,000 treated patients were antineoplastics (88.4 cases/1,000 patients), immunosuppressants (8.2 cases/1,000 patients), antithrombotics (3.9 cases/1,000 patients) and antidiabetics (3.7 cases/1,000 patients). Acenocoumarol (51 cases), insulin (45 cases), acetylsalicylic acid (20 cases) and ibuprofen (15 cases) were most common non-antineoplastic drugs. Platin-combinations (24 cases) and doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide (12 cases) were the most prevalent chemotherapy schemes.

Treatment was stopped in 255/509 cases (50.1%), continued in 89/509 cases (17.5%), switched for another drug in 69/509 cases (13.5%) and the dose or dosage schedule was changed in 96/509 cases (18.9%).

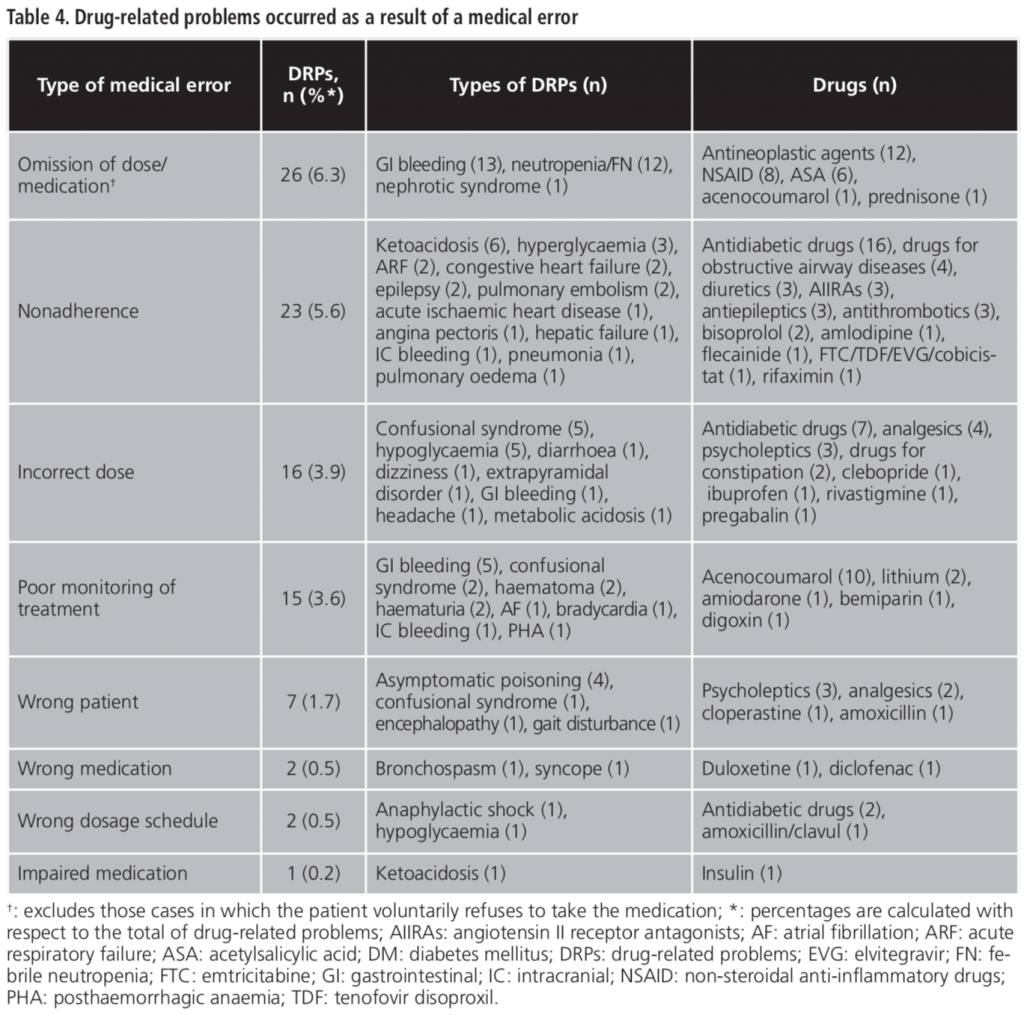

Medical errors

In 90 hospital admissions (22.8%) were detected at least one ME. Table 4 shows the 92 preventable DRPs and the implicated drugs according to the type of ME. Omission of dose or medication and nonadherence were the most frequent and caused 26 (6.3%) and 23 (5.6%) of DRPs, respectively. Gastrointestinal bleeding occurred in 19 MEs (20.6%). Antidiabetics (26 cases), antithrombotics (21 cases) and antineoplastic agents (12 cases) were most common groups, whereas insulin (18 cases), acenocoumarol (12 cases) and acetylsalicylic acid (6 cases) were most frequently implicated drugs.

Outcomes

The median (IQR) length of stay was 4.0 (2.0-6.0) days. In nine hospital admissions (2.3%), the patients were transferred to the intensive care unit. Nineteen patients (5.0%) died during the hospitalisation, ten of whom (52.6%) due to DRPs and nine (47.4%) due to other causes. Among the 390 DRPs which did not have a fatal outcome, 265 cases (67.9%) patients recovered, 65 cases (16.7%) patients were recovering and 60 cases (15.4%) patients recovered with sequels at hospital discharge. Twenty-one cases were reported to the Spanish Pharmacovigilance System for medicinal products for human use due to their severity or rarity.

Discussion

In this study, developed in the context of an integral risk management plan of drugs and proactive pharmacovigilance, we reported the prevalence, preventability and outcomes of DRPs causing hospitalisation. It is a retrospective analysis and the included cases have been identified on the basis of data in electronic healthcare records, which may imply an underestimation of the real DRP prevalence. Moreover, as an observational study, it may be subject to residual confounding and unmeasured factors. All these aspects might bias our findings and limit indirect comparisons with other studies. Nevertheless, we believe that our study provides some interesting and current information regarding drug-related hospitalisations, which can prove useful to reinforce the safe use of medicines.

Our data show that up to 4.7% of all assessed hospital admissions were associated with DRPs. The median length of stay was four days, being quite lower than that reported by other studies8. A large proportion of patients aged ≥65 years, were polymedicated (≥4 drugs) and presented multiple chronic conditions (CRG core health statuses 6 to 9), which are at high risk of debility, developing DRPs and using future resources10,15. More frequently hospitalisations were due to gastrointestinal, endocrine and haematological side effects. Gastrointestinal bleeding owing to antithrombotic drugs, mainly acenocoumarol, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAID) and acetylsalicylic acid was the most common DRP that resulted in admission. The second most frequent cause was due to neutropenia associated with chemotherapy. Previous studies conducted by our team were focused specifically in these groups of drugs16-18.

As indicated above, antithrombotic and antineoplastic drugs were the most frequently involved, followed by cardiovascular agents and antidiabetics. Our results coincide with the available evidence that identifies them as the major groups of medicines causing hospitalisation6,15,19,20. However, the order of the implicated drugs may be a direct consequence of how commonly they are used. To the best of our knowledge, most of the studies have not estimated the prevalence based on consumption data or population at risk. Therefore, we have thought it was interesting to calculate the rate of DRPs by the number of treated patients. Taking into account this consideration, immunosuppressants were the second most prevalent group, after antineoplastics. Previously, immunosuppressive agents were also found as one of the major causal groups of hospital admissions15. Concerning the duration of implicated drugs we have defined four exposure types. The majority of cases were associated with a long-term or chronic use. These findings reinforce the need for an ongoing review of treatments.

A wide variability in the prevalence rates of drug-related hospitalisations has been reported in the scientific literature as a consequence of differences in the methodology used in each study. Prospective studies are associated with higher prevalence rates than those retrospective6,19. This may partially explain that the prevalence in our study is slightly below the lower limit of the estimated median range of 5-10%6-8,15. Likewise, heterogeneity in how drug-related events are defined is likely to account for much of this variability. Several studies used classical ADR definitions as inclusion criteria, such as proposed by the World Health Organization (WHO) or Edwards and Aronson7,8,20,21, but these ones are rather restrictive and exclude other drug events that result in hospitalisation. Recently, ADR definition has been extended by the new European pharmacovigilance regulations. It includes any harmful and unintentional response to a drug, taking account of adverse reactions derived from any use outside of the marketing authorization terms, abuse and MEs22. This new reorientation is closer to the DRP concept, which is used in scientific publications and also takes into account noncompliance, supratherapeutic dosages and untreated indications5,6,15,23. However, such as other studies13, deliberate overdoses or patients who were admitted for attempting suicide using medications were not included in the present analysis. As far as we are concerned, these cases are more related to the social-psychological status of patients than to a direct pharmacotherapeutic problem and should not be considered as DRPs.

The impact of DRPs could also be the result of different detection methods and specialties of the included departments21. The proactivity is the cornerstone of the care quality program in which the current study was conducted. This is fundamentally because of reporting systems consistently underestimating the burden of DRPs as a cause of hospital admission5, where it was showed in a study that underreporting was up to 100%21. This proactivity is being carried out using the EIS and exploiting the available data. Concretely, as previous studies18, the information management tool of the hospital electronic medical history was used for cases detection. This tool uses search filters (date ranges, free text words, ICD diagnostic codes, etc.) to narrow down the cases of interest among all hospital episodes. Some authors have pointed that retrospective analyses based on routine detection of DRPs on medical records and by using information systems based on ICD codes may underestimate the real prevalence of drug-related hospitalisations20,21. Nevertheless, it has been recently demonstrated the high sensitivity and specificity of the data crossing from EIS for the proactive detection of ADR24.

Moreover, while the prevalence of drug-related hospitalisations has been well studied in adults and the elderly6,8,20,21,23,25, much less is known in paediatrics. We reported a prevalence of 1.5% in the paediatric population. Previously, a prospective single-centre study found a prevalence of 2.4% in pediatric patients not exposed to chemotherapy, being considerably higher in those exposed26. Pediatric cancer patients in our health department are referred to other hospitals. Likewise, we should bear in mind that some medical departments were not included in the present analysis. The vast majority of these hospitalisations were related to surgical procedures. Although we cannot rule out that there were no DRPs in these patients, we considered that they should not be included as a real population at risk. Their inclusion would considerably increase the cases needed to be reviewed and it would entail a distorted reduction of DRP prevalence.

On the other hand, among the detected DRPs, of special interest those are preventable and which could have been avoided. By definition, preventable events are those caused by MEs12. The percentage of preventability in our cohort was similar than that previously reported by some authors25,27. However, in most studies, prevention rates were remarkably higher (up to 90%)8,21,23,28. In some of them, preventability was determined using the Hallas methodology8,28, whereas in others, drug-related hospitalisations were supposed to be potentially avoidable because they were considered dose-related23. In any case, although the percentage of preventable events observed in our study may seem low, their health impact is really worrying.

Omission of a dosage or medication and nonadherence were most common MEs and represented 11.9% of the total DRPs. In the same way, other studies have also pointed noncompliance as one of the main causes leading to hospitalisation6,23. Antidiabetic agents and drugs for obstructive airway diseases were the most commonly related to noncompliance in our study, which agree on prior data that showed a lowest adherence in diabetes and pulmonary disease29. Nonadherence may have a negative impact on patient health and on the healthcare system as a whole. Consequently, it is important to signal nonadherence, to detect possible reasons and to establish tailored interventions30. Personal history of noncompliance with medical treatments is encoded in the ICD-10 as Z91.1 and its inclusion in the electronic medication history would help to better identify this problem.

Regarding DRPs due to treatment omission, which includes the lack of prophylaxis, most of the hospitalisations were due to gastrointestinal bleeding in patients treated with gastrolesive treatments (NSAID and antithrombotic drugs) and neutropenia induced by chemotherapy. In these cases, as it was also observed before16,17, gastroprotection and granulocyte-colony stimulating factors had prophylactic indication, but were not used.

Finally, as it has been indicated by other authors21, developing mechanisms to provide feedback on the recording of DRPs to physicians should be considered. That is why the main results of this study, as well as those of preceding studies17,18, have been communicated by the corporate electronic noticeboard to all the hospital and primary health area agents. But multidisciplinary interventions aimed at increasing patients knowledge, especially focused to improve adherence and self-medication, are also necessary. Altogether, as part of a healthcare quality programme, serve to improve the safe use of treatments.

Conclusions

Serious DRPs require admission to hospital, resulting in drug-related deaths and considerable use of health resources. In detected cases, antithrombotic, antineoplastic, cardiovascular and antidiabetic drugs were the most common groups causing hospitalisation. Most of the patients were admitted due to digestive, endocrine and blood DRPs. Moreover, the percentage of preventable DRPs was not negligible and they were mainly related to the omission of a dosage or medication and nonadherence. Feedback of our results to health area agents and the implementation of corrective interventions can serve as a basis on which to reinforce the safe use of medicines.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Bibliography

1. Barker KN, McConnell WE. The problems of detecting medication errors in hospitals. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1962;19:360-9.

2. Manasse HR Jr. Medication use in an imperfect world: drug misadventuring as an issue of public policy, Part 1. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1989;46(5):929-44.

3. Manasse HR Jr. Medication use in an imperfect world: drug misadventuring as an issue of public policy, Part 2. Am J Hosp Pharm. 1989;46(6):1141-52.

4. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS, eds. To err is human: building a safer health system. Washington, DC: National Academy Press (US); 2000. p. 1-312.

5. Manias E. Detection of medication-related problems in hospital practice: a review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;76(1):7-20.

6. Al Hamid A, Ghaleb M, Aljadhey H, Aslanpour Z. A systematic review of hospitalization resulting from medicine-related problems in adult patients. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2014;78(2):202-17.

7. Beijer HJ, de Blaey CJ. Hospitalisations caused by adverse drug reactions (ADR): a meta-analysis of observational studies. Pharm World Sci. 2002;24 (2):46-54.

8. Pirmohamed M, James S, Meakin S, Green C, Scott AK, Walley TJ, et al. Adverse drug reactions as cause of admission to hospital: prospective analysis of 18 820 patients. BMJ. 2004;329(7456):15-9.

9. Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-45.

10. Hughes JS, Averill RF, Eisenhandler J, Goldfield NI, Muldoon J, Neff JM, et al. Clinical Risk Groups (CRGs): a classification system for risk-adjusted capitation-based payment and health care management. Med Care. 2004;42(1):81-90.

11. Schumock GT, Thornton JP. Focusing on the preventability of adverse drug reactions. Hosp Pharm. 1992;27(6):538.

12. Otero MJ, Codina C, Tamés MJ, Pérez M. Errores de medicación: estandarización de la terminología y clasificación. Resultados de la Beca Ruiz Jarabo 2000. Farm Hosp. 2003;27(3):137-49.

13. Asseray N, Ballereau F, Trombert-Paviot B, Bouget J, Foucher N, Renaud B et al. Frequency and severity of adverse drug reactions due to self-medication: a cross-sectional multicentre survey in emergency departments. Drug Saf. 2013;36(12):1159-68.

14. Lewis SC, Langman MJ, Laporte JR, Matthews JN, Rawlins MD, Wiholm BE, et al. Dose-response relationships between individual nonaspirin nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NANSAIDs) and serious upper gastrointestinal bleeding: a meta-analysis based on individual patient data. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2002;54(3):320-6.

15. Nivya K, Sri Sai Kiran V, Ragoo N, Jayaprakash B, Sonal Sekhar M. Systemic review on drug related hospital admissions -A pubmed based search. Saudi Pharm J. 2015;23(1):1-8.

16. Koninckx M, Marco JL, Pérez I, Faus MT, Peiró E. Risk factors for febrile neutropenia admissions associated with chemotherapy. Eur J Clin Pharm. 2016; 18(4):223-31.

17. Marco JL, Koninckx M, Pérez I, Faus M, Fuster R, Moncho M. Cross-sectional analysis of retrospective case series of hospitalisations for gastropathy caused by non-steroidal anti-inflammatory treatment: risk factors and gastroprotection use. Eur J Hosp Pharm. 2017;24(6):355-60.

18. Marco JL, Koninckx M, Pérez I, Faus MT, Perea M. Hospital admissions for bleeding events associated with treatment with apixaban, dabigatran and rivaroxaban. Eur J Hosp Pharm. Published Online First: 30 October 2017.

19. Bénard-Laribière A, Miremont-Salamé G, Pérault-Pochat MC, Noize P, Haramburu F. Incidence of hospital admissions due to adverse drug reactions in France: the EMIR study. Fundam Clin Pharmacol. 2015;29(1):106-11.

20. Alhawassi TM, Krass I, Bajorek BV, Pont LG. A systematic review of the prevalence and risk factors for adverse drug reactions in the elderly in the acute care setting. Clin Interv Aging. 2014;9:2079-86.

21. Brvar M, Fokter N, Bunc M, Mozina M. The frequency of adverse drug reaction related admissions according to method of detection, admission urgency and medical department specialty. BMC Clin Pharmacol. 2009;9. [citado 20 agosto 2018]. Disponible en: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC 2680808/.

22. Boletín Oficial del Estado. Real Decreto 577/2013, de 26 de julio, por el que se regula la farmacovigilancia de medicamentos de uso humano. BOE núm. 179 de 27/7/2013.

23. Singh H, Kumar BN, Sinha T, Dulhani N. The incidence and nature of drug-related hospital admission: a 6-month observational study in a tertiary health care hospital. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. 2011;2(1):17-20.

24. Marco JL, Koninckx M, Faus MT, Pérez I, Bourgon L. Detection of serious suspected adverse reactions associated with direct oral anticoagulants through two proactive pharmacovigilance systems. Eur J Clin Pharm. 2018; 20(3):133-9.

25. Schmiedl S, Rottenkolber M, Szymanski J, Drewelow B, Siegmund W, Hippius M, et al. Preventable ADRs leading to hospitalization -results of a long-term prospective safety study with 6,427 ADR cases focusing on elderly patients. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2018;17(2):125-37.

26. Posthumus AA, Alingh CC, Zwaan CC, van Grootheest KK, Hanff LLM, Witjes BBCM, et al. Adverse drug reaction-related admissions in paediatrics, a prospective single-centre study. BMJ Open. 2012;2. [citado 20 agosto 2018]. Disponible en: https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/2/4/e000934.

27. Kalisch LM, Caughey GE, Barratt JD, Ramsay EN, Killer G, Gilbert AL, et al. Prevalence of preventable medication-related hospitalizations in Australia: an opportunity to reduce harm. Int J Qual Health Care. 2012;24(3):239-49.

28. Geer MI, Koul PA, Tanki SA, Shah MY. Frequency, types, severity, preventability and costs of Adverse Drug Reactions at a tertiary care hospital. J Pharmacol Toxicol Methods. 2016;81:323-34.

29. DiMatteo MR. Variations in patients’ adherence to medical recommendations: a quantitative review of 50 years of research. Med Care. 2004; 42(3):200-9.

30. Hugtenburg JG, Timmers L, Elders PJ, Vervloet M, van Dijk L. Definitions, variants, and causes of nonadherence with medication: a challenge for tailored interventions. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2013;7:675-82.

____