Cantillana-Suárez MG, Galván-Banqueri M, Artacho-Criado S, Sánchez-Fidalgo S

Servicio de Farmacia. Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme. Sevilla (España)

Fecha de recepción: 20/05/2018 – Fecha de aceptación: 18/07/2018

Correspondencia: María de Gracia Cantillana Suárez w Hospital Universitario Virgen de Valme (Servicio de Farmacia) w Avda. de Bellavista, s/n w 41014 Sevilla (España)

mariag.cantillana.sspa@juntadeandalucia.es

____

Summary

Objective: In patients with relapse and/or refractory Multiple myeloma (MM), bortezomib- and lenalidomide-based regimens are the most commonly used in combination with corticosteroids, but it is changing rapidly. Currently, two proteasome inhibitors have been authorized by the European Medicines Agency (EMA): carfilzomib and ixazomib. This study aimed to compare the relative efficacy of carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone and ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone in patients with relapse MM through indirect treatment comparisons (ITCs).

Method: A search was made up to January 2018. Databases consulted were MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library and the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that compared the efficacy of carfilzomib or ixazomib versus a common treatment comparator, in which outcomes of overall survival (OS), progression free survival (PFS), and overall response rate (ORR) were considered. ITCs were carried out using the method proposed by Bucher et al.

Results: Two RCTs were included. The results of the adjusted ITCs showed that there were no statistically significant differences between the two combinations in terms of PFS [HR (CI 95%): 0.93 (0.69-1.26)] and ORR [RR (CI 95%): 1.19 (0.79-1.79)]. OS was not reached in either study group in neither clinical trials.

Conclusions: The ITCs indicates no difference in efficacy between both treatments. Although there should be an independent, head to head trial of both drugs to confirm the results. Therefore, other considerations such as safety, tolerance and cost-effectiveness should be taken into account in order to select the most appropriate treatment for individuals with multiple myeloma.

Key words: Carfilzomib, ixazomib, multiple myeloma, comparison.

____

Introduction

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a clonal disease of plasma cells that results in abnormal bone marrow plasma cells and immunoglobulin or light chain overproduction, which can cause end-organ damage such as bone marrow failure, bone destruction, hypercalcaemia, anaemia, infection, renal failure, and neurological symptoms. It constitutes approximately 1% of all reported neoplasms and 13% of hematologic cancers worldwide1. In Europe, the estimated annual incidence is 38,930 new cases with approximately 24,290 deaths and the incidence is expected to increase over the next decade2.

Prognosis varies considerably on the basis of several factors, including the presence of cytogenetic abnormalities3. MM with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, del(17), t(14;16) and/or t(4;14), is characterized by short survival related to an early relapse rate and rapid development of mechanisms of resistance to multiple agents. Del (17), typically considered the ultra-high-risk group occurs in approximately 10-12% of patients with Refractory/Relapsed Multiple Myeloma (RRMM)4,5.

Treatment with cytotoxic drugs, such as alkylating agents and anthracyclines, and corticosteroids, was given in the past until the introduction of the first-in-class proteasome inhibitor, bortezomib, and the immunomodulatory drugs, thalidomide and lenalidomide that led to improved outcomes. First line treatment options contain at least one of the novel therapies, i.e. proteasome inhibitors and/or immunostimulatory drugs, followed by autologous stem cell transplantation (ASCT), if indicated6. These novel agents and the introduction of ASCT have substantially improved overall survival (OS), which currently ranges from 5 to 7 years7. In younger patients treated with immunomodulatory drugs plus proteasome inhibitor before and after ASCT, median progression-free survival (PFS) may be over 5 years and median OS may exceed 10 years8-10.

In the relapsed and/or refractory patients, bortezomib- and lenalidomide-based regimens are the most commonly used in combination with corticosteroids, but it is changing rapidly for two reasons. Firstly, lenalidomide and bortezomib are currently used in frontline treatment and many patients become resistant to these agents early in the course of their disease. Secondly, six second-line new agents have been recently developed and offer new possibilities (pomalidomide, carfilzomib, ixazomib, panobinostat, elotuzumab and daratumumab)11.

The second/third lines treatment varies according to the duration of the previous response and the drugs already given12. Response rates decrease with every successive relapse (defined by the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) as previously treated myeloma patients who, after a period of being off-therapy, require salvage therapy): 58% at 1st relapse to 15% at 4th relapse.

Currently, two proteasome inhibitors have been authorized by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) with the following indications:

– Carfilzomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone or dexamethasone alone is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with MM who have received at least one prior therapy13.

– Ixazomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone is indicated for the treatment of adult patients with MM who have received at least one prior therapy6.

The proteosoma inhibitors were approved for the treatment of relapse MM in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone on the basis of results from phase 3 trials, showing improved progression-free survival (PFS) as compared with lenalidomide and dexamethasone. Both clinical trials reinforce the evidence in support of using a triplet regimen is more efficacious than doublet regimens.

Given the lack of head-to-head trials comparing both proteasome inhibitors, performing an indirect comparison could be an alternative to explore the relative efficacy of these drugs. Indirect treatment comparisons (ITCs) are relatively new approaches to evaluate the relative treatment effect when two or more interventions have not been compared directly. An adjusted indirect comparison is an indirect comparison of different treatments, adjusted according to the results of their direct comparison with a common control in order that the strength of the randomised trials is preserved. So, an indirect comparison of carfilzomib versus ixazomib has been performed.

Empirical evidence indicates that results of adjusted indirect comparison are usually, but not always, consistent with the results of direct comparisons. In the absence of head-to-head trials, an indirect comparison is the best way to estimate the treatment effect between two interventions, albeit with greater uncertainty than in direct head-to-head randomised controlled trials. These approaches are being increasingly used by health technology assessment (HTA) agencies as new and existing drugs must be evaluated within the context of all available clinical evidence14.

The main objective of this study was to compare the relative efficacy of carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone and ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone in patients with relapse MM through ITCs.

Method

A literature search was carried out to identify relevant studies published (January 2018). Databases consulted were MEDLINE (through OVID), the Cochrane Library and the databases of the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD). Free terms were used.

Grey literature was obtained by searching the web sites of the European Medicines Agency (EMA) and Agencia Española de Medicamentos y Productos Sanitarios (AEMPS).

Studies were chosen for inclusion in the review based on the criteria outlined below:

– Population: patients with MM.

– Intervention: carfilzomib or ixazomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

– Comparator: placebo in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone.

– Outcomes: OS, PFS and overall response rate (ORR).

– Study design: randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

Selection, critical appraisal, data extraction, qualitative and quantitative synthesis of the evaluated studies was independently undertaken by two researchers.

Assessment of bias in RCTs was completed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool15.

Both clinical similarity and methodological similarity were considered in adjusted indirect comparisons14,16. Also, if there were direct and indirect comparisons, consistency should have been accounted for. Finally, adjusted ITCs were conducted based on the relative effects of each drug against a common comparator following the method proposed by Bucher et al.17 The software CIT, developed by the Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health (CADTH), was used to calculate the risk ratio (HR and RR) (95% CI)17,18.

Results

A total of 400 citations were found, of which 49 were clinical trials. Six of them met inclusion criteria (four for carfilzomib and two for ixazomib). Finally, two RCTs were included because they have a common comparator19,20.

Stewart et al. 2015 was a randomized, open-label, multicentre, phase 3 study which evaluated the safety and efficacy of carfilzomib with lenalidomide and weekly dexamethasone as compared with lenalidomide and weekly dexamethasone alone in patients with relapsed MM. A total of 792 patients were included. The primary end point was PFS19.

Moreau et al. 2016 was a phase 3, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial reported that evaluated the efficacy and safety of ixazomib, administered weekly, plus lenalidomide–dexamethasone with those of placebo plus lenalidomide–dexamethasone in patients with relapsed, refractory, or relapsed and refractory MM. A total of 722 patients were included. The primary end point was PFS20.

Stewart et al. study was judged to have a low risk of bias except in the domain of incomplete outcome measures (unclear risk of bias). Moreau et al. study was judged to have a low risk of bias except in the domain of incomplete outcome measures (unclear risk of bias).

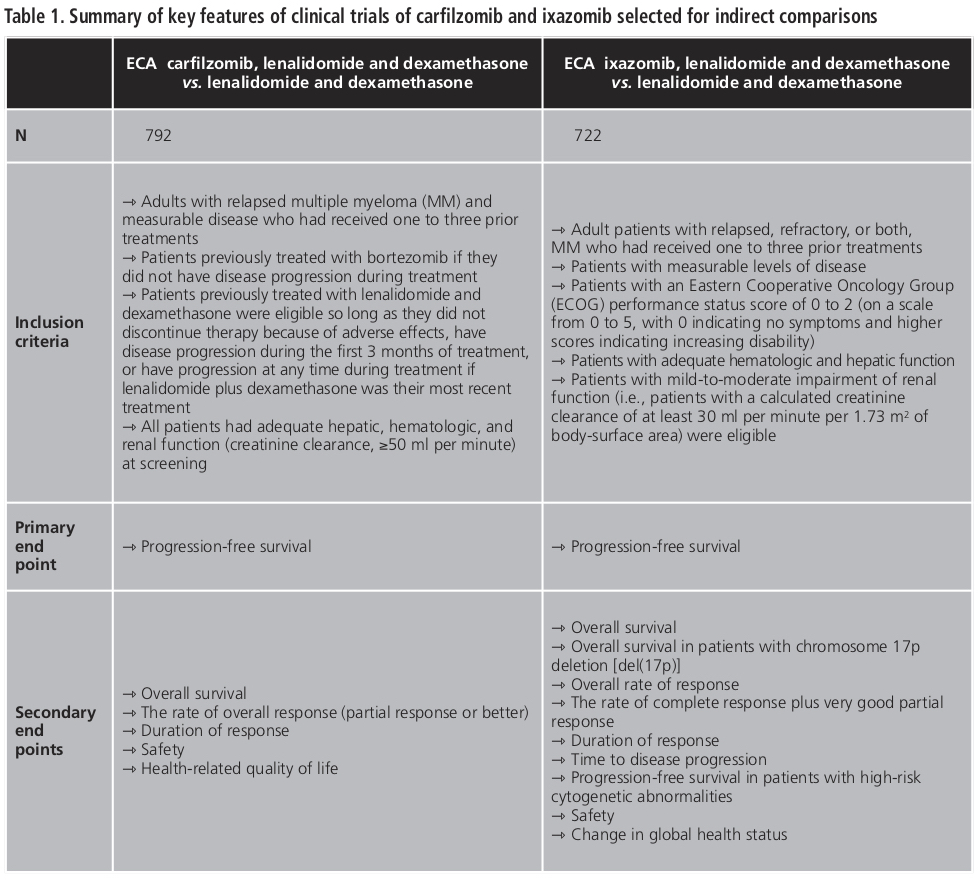

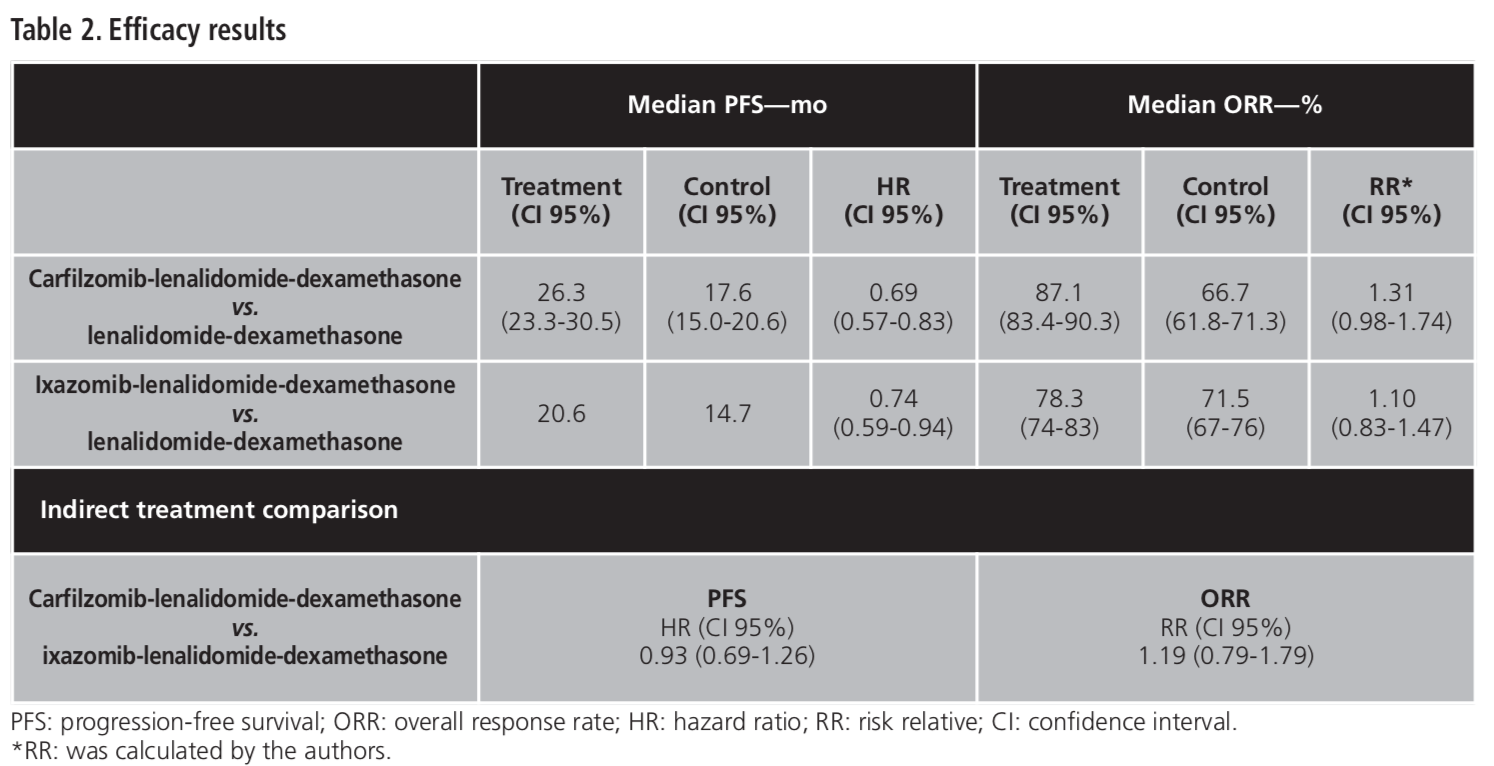

Summary of key features of both clinical trials is shown in Table 1. So, similarity assumptions were shown to be true.

To assess the relative efficacy of the drugs, relevant and common clinical end point in the studies were selected: OS, PFS and the ORR. However, finally OS was not selected because it was not reached in either study group in neither clinical trials.

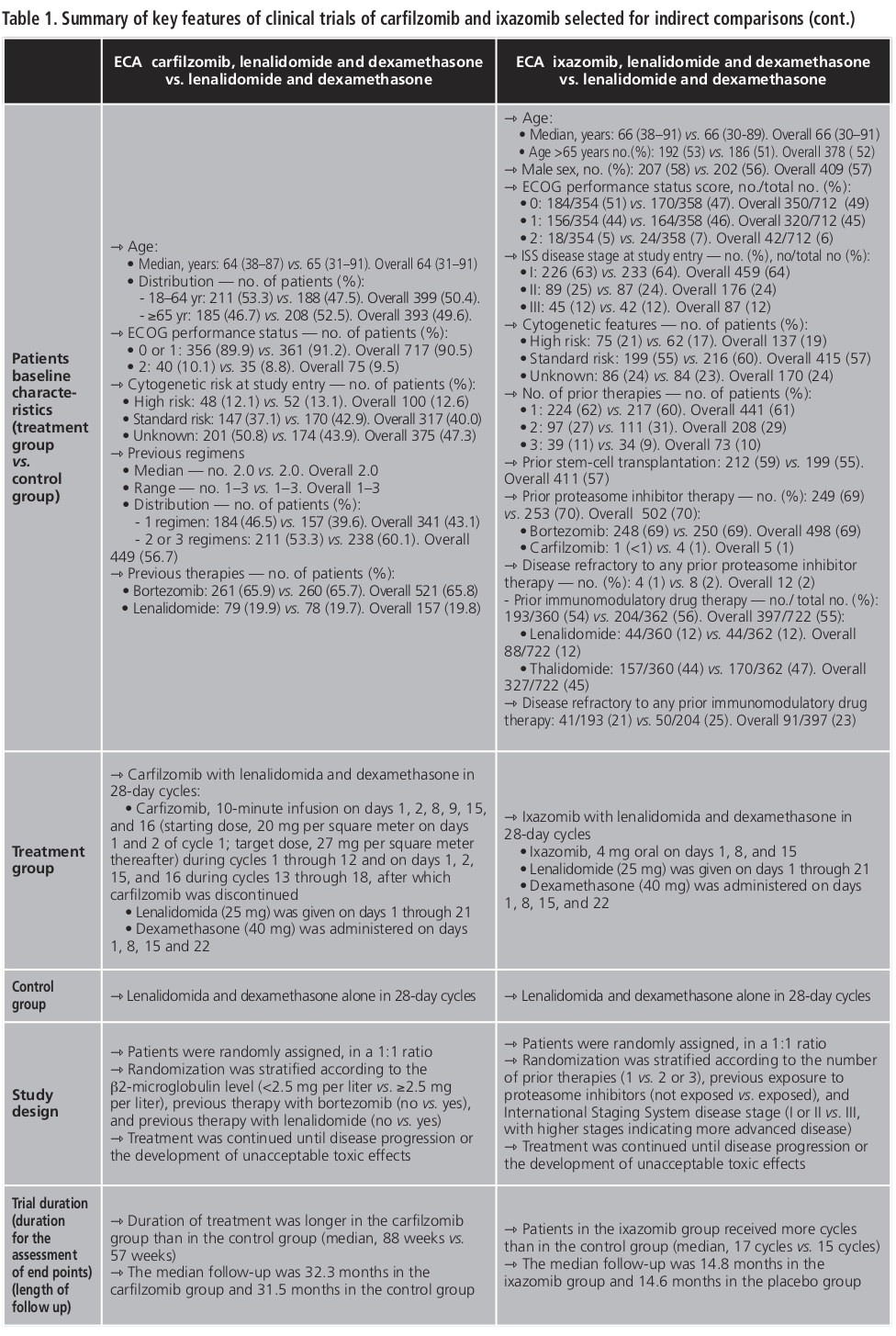

The efficacy results for the selected end points are shown in Table 2. The results of the adjusted ITCs revealed that:

– For PFS, HR (CI 95%) carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone vs. ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone was 0.93 (0.69-1.26). So, there were no statistically significant differences between the two treatments in terms of PFS.

– For ORR, RR (CI 95%) carfilzomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone vs. ixazomib-lenalidomide-dexamethasone was 1.19 (0.79-1.79). So, there were no statistically significant differences between the two treatments in terms of ORR.

Discussion

Based on the similarity of the two RCTs included, it was possible to realize indirect comparisons between the two drugs.

As for the strength of this study, the internal validity of findings was high. Studies did not differ substantially with respect to the number of patients, the characteristics of the patients, the way in which the outcomes were measured or defined, the protocol requirements including the concomitant interventions allowed, as well as similar follow-up procedures. It was not possible to assess external validity of findings as there was no direct evidence to compare with.

There are several limitations to consider in this analysis. Firstly, there are some differences in the inclusion criteria for each RCT. Regarding prior therapies of patients, Stewart et al. included patients had received one to three prior treatments, which were bortezomib and lenalidomide-dexamethasone if they did not have disease progression during treatment or not discontinue therapy because of adverse effects19. On the other hand, Moreau et al., although also included patients had received one to three prior therapies, these were not specified20. Secondly, randomization strategy was different. Stewart et al. stratified patients according to the β2-microglobulin level (<2.5 mg per liter vs. ≥2.5 mg per liter), previous therapy with bortezomib (no vs. yes), and previous therapy with lenalidomide (no vs. yes) and Moreau et al. according to the number of prior therapies (1 vs. 2 or 3), previous exposure to proteasome inhibitors (not exposed vs. exposed), and International Staging System disease stage (I or II vs. III, with higher stages indicating more advanced disease). Thirdly, a higher number of patients with high risk features defined by FISH were enrolled in the ixazomib study as compared to the carfilzomib study (21% vs. 12%) and a higher rate of patients previously exposed to lenalidomide (20%) was enrolled in the carfilzomib study trial in comparison with the ixazomib study (12%). Finally, for the ixazomib study, the median follow-up was 14.8 months vs. 14.6 months in the placebo group, whereas for the carfilzomib study, the median follow-up was longer (32.3 vs. 31.5 months)19,20. This fact could influence the results of the indirect comparison.

The statistical approach employed is widely accepted by agencies such as the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE), and the CADTH. However, many clinicians may be unfamiliar with this approach and few guidelines are available to critically appraise such studies.

Given the lack of ITCs related to these drugs, this work could be a contribution to the evidence available so far. However head-to-head trials are necessary to select the best treatment option.

Conclusion

The ITCs indicates no difference in efficacy between both treatments. Although there should be an independent, head to head trial of both drugs to confirm the results. Therefore, other considerations such as safety, tolerance and cost-effectiveness should be taken into account in order to select the most appropriate treatment for individuals with multiple myeloma.

Conflict of interests: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Palumbo A, Bringhen S, Ludwig H, Dimopoulos MA, Bladé J, Mateos MV, et al. Personalized therapy in multiple myeloma according to patient age and vulnerability: a report of the European Myeloma Network (EMN). Blood. 2011;118:4519-4529.

2. Ferlay J, Steliarova-Foucher E, Lortet-Tieulent J, Rosso S, Coebergh JWW, Comber H, et al. Cancer incidence and mortality patterns in Europe: estimates for 40 countries in 2012. Eur J Cancer. 2013;49:1374-403.

3. Rajkumar SV, Harousseau JL, Durie B, Anderson KC, Dimopoulos M, Kyle R, et al. Consensus recommendations for the uniform reporting of clinical trials: report of the International Myeloma Workshop Consensus Panel 1. Blood. 2011;117:4691-5.

4. Avet-Loiseau H, Magrangeas F, Minvielle S, Moreau P, Attal M, Campion L, et al. Long-term analysis of the IFM 99 trials for myeloma: cytogenetic abnormalities [t(4;14), del(17p), 1q gains] play a major role in defining long-term survival. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:1949-1952.

5. Avet-Loiseau H, Soulier J, Fermand JP, Yakoub-Agha I, Attal M, Hulin C, et al. Impact of highrisk cytogenetics and prior therapy on outcomes in patients with advanced relapsed or refractory multiple myeloma treated with lenalidomide plus dexamethasone. Leukemia. 2010;24:623-628.

6. European Medicine Agency. EPAR-Public Assessment Report. Ninlaro® (Ixazomib). In: European Medicine Agency (EMA). 2016. EMEA/H/C/003844/ 000. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/003844/WC500217623.pdf. Accessed 20 Dec 2017.

7. Van de Donk NW, Lokhorst HM. New developments in the management and treatment of newly diagnosed and relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma patients. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013;14:1569-1573.

8. Palumbo A, Cavallo F, Gay F, Cerrato C, Genuardi M, Omedé P, et al. Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:895-905.

9. Gay F, Oliva S, Petrucci MT, Conticello C, Catalano L, Corradini P, et al. Chemotherapy plus lenalidomide versus autologous transplantation, followed by lenalidomide plus prednisone versus lenalidomide maintenance, in patients with multiple myeloma: a randomised, multicentre, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16:1617-1629.

10. Attal M, Lauwers-Cances V, Hulin C, Leleu X, Caillot D, Escoffre M, et al. Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone with Transplantation for Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1311-1320.

11. Moreau P. How I treat: New agents in myeloma. Blood. 2017. doi: 10.1182/blood-2017-05-743203.

12. Moreau P, San Miguel J, Ludwig H, Mateos V, Zamagni E, Avet-Loiseau H, et al (European Society for Medical Oncology [ESMO] Guidelines Working Group). Multiple myeloma: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2013;2:33-37.

13. European Medicine Agency. EPAR-Public Assessment Report. Kyprolis® (Carfilzomib) In: European Medicine Agency (EMA). 2015. EMEA/H/ C/003790/ 0000. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/ EPAR_-_Public_assessment_report/human/003790/WC500197694.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2017.

14. Guidance document on reporting indirect comparisons. Ottawa: CADTH; 2015.

15. Higgins JPT, Green S. Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions Version 5.1.0 In: The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. http://www.cochrane-handbook.org. Accesed 15 Dec 2017.

16. Ortega A, Fraga MD, Alegre-del-Rey EJ, Puigventos-Latorre F, Porta A, Ventayol P, et al. A checklist for critical appraisal of indirect comparisons. Int J Clin Pract. 2014;68:1181-1189.

17. Bucher HC, Guyatt GH, Griffith LE, et Walter SD. The results of direct and indirect treatment comparisons in meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. J Clin Epidemiol. 1997;50:683-691.

18. Wells GA, Sultan SA, Chen L, et al. Indirect Treatment Comparisons (ITC). In: Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health. 2012. https:// www. cadth.ca/resources/itc-user-guide/download-software-win-xp. Accessed 2 Aug 2017.

19. Stewart AK, Rajkumar SV, Dimopoulos MA, Masszi T, Špička I, Oriol A, et al. Carfilzomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone for relapsed multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:142-152.

20. Moreau P, Masszi T, Grzasko N, Bahlis NJ, Hansson M, Pour L, et al. Oral Ixazomib, Lenalidomide, and Dexamethasone for Multiple Myeloma. N Engl J Med. 2016;374: 1621-1634.

____